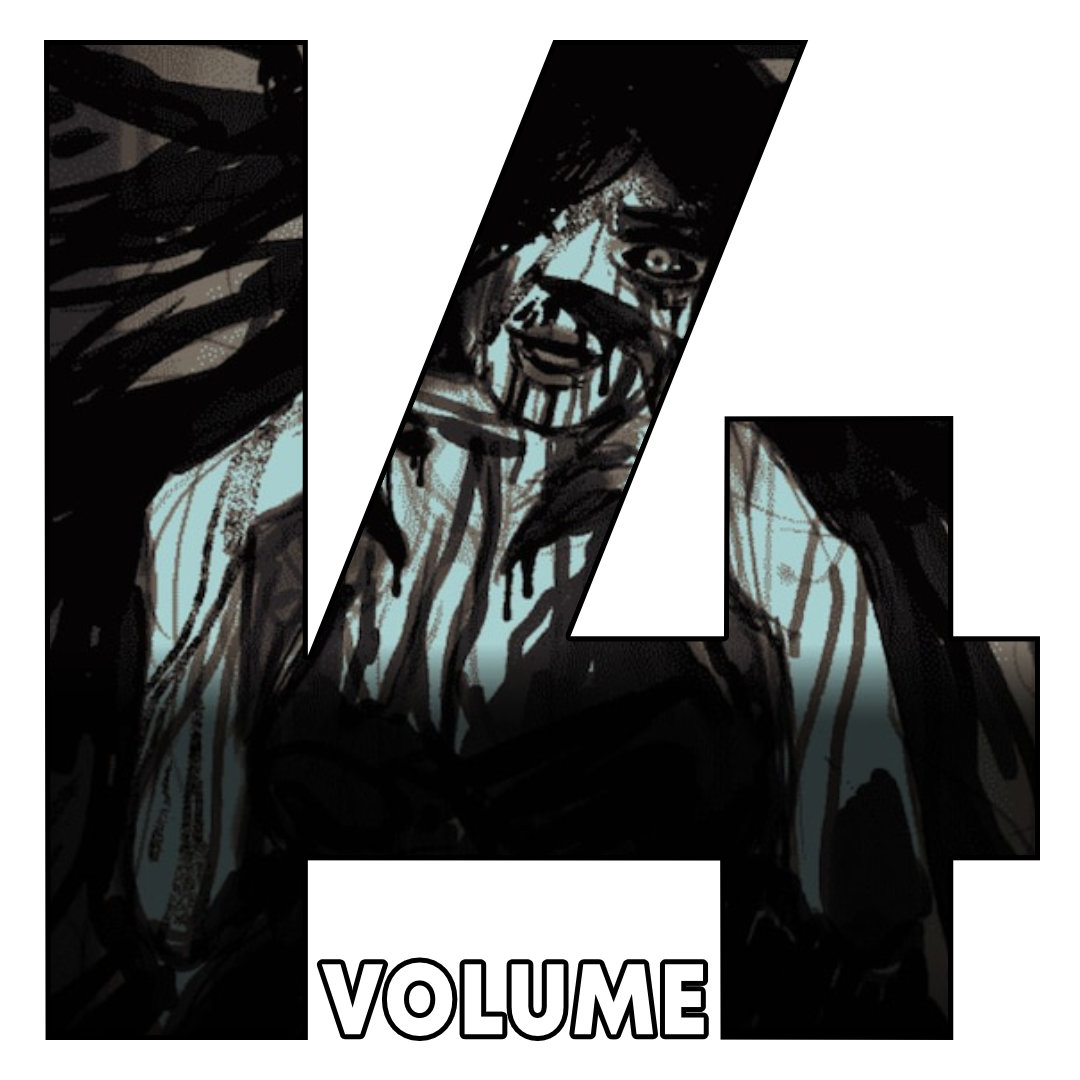

Historian Dr Cat Beck celebrates and explores the effective and sensitive portrayal of late 8th century mental illness in Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice.

NB: Cane and Rinse recommends that you play through Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice before reading on.

We get used to seeing sufferers of mental illness as colourful set-dressing in games that depict the past.

Think of the gibbering beggars who attack you unprovoked in Assassins Creed or the whole ‘Mind of Madness’ quest in Skyrim. There’s an underlying feeling that throwing in a few lunatics, alongside the prostitutes and beggars, gives a grittier feel to historical streets, a feat only bested by littering the cobbles with plague victims or dung heaps.

After all, the common narrative is that the past was a hard, brutal place and nothing says it better than a lack of state provisioned social care or sanitation. But by using madness in this way historical games fall prey to the othering of the mentally ill which occurred all too frequently in previous centuries. Whether someone hearing voices was considered cursed, possessed, weak-minded or bestial, many historical interpretations of mental illness dehumanised sufferers.

This is compounded in our portrayals of madness by the fact that much of our understanding is gathered from what magistrates, priests or physicians wrote down about sufferers. Very rarely do we get glimpses into an individual’s experience of their illness. Perhaps because of this, depictions of historical mental illness all too frequently are one-dimensional, stereotypical and alienating in a way which underpins our modern anxieties about the current mental health crisis. People in the past were tougher, because they had to be, right?

But as I’m sure everyone reading this can attest to, mental illness has nothing to do with weakness of mind or character. This idea that people in the past were somehow numbed to their surroundings or so occupied by the general graft of living that they had no time to indulge in mental instability is extremely damaging not just to our understanding of historical madness but also to our modern conception of mental illness. The truth is that humans have always suffered from mental disorders and when you spend a lot of time scouring historical material for tantalizing flashes of individual experience it’s plain to see that despite vastly different contexts, people are always just people.

It’s here that games are uniquely well-positioned to explore history. They offer the player an active, immersive and highly personal experience of a different time. They allow us to connect with individuals easily lost in the historical record, often all that remains of their experience is their name in a register, a straightjacket or a set of trepanning drills used to release demons from the brain.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice is a gut-wrenchingly evocative example of just how effective sensitively exploring mental illness in a historical setting can be.

Released in August 2017 and widely praised in both the gaming and scientific community, Ninja Theory with the support of the Wellcome Trust delivered a game rich in the visceral, personal experience of psychosis.

Hellblade follows Senua, a eighth-century Pictish warrior, as she journeys into the heart of Norse ‘Helheim’ to save the soul of her murdered lover from the goddess Hela. Senua is plagued by shadowy projections of the violent Norsemen who massacred her village and fights against an internal darkness which threatens to consume her. She is also accompanied by clamouring voices who laugh and criticise her at every turn as well as goading her on and providing sometimes vital tips for how to proceed.

The game mechanics revolve around her fractured reality as the player is encouraged to see meaning in the convergence of shadows and scenery around her or to align splintered images of an impassable route to uncover a bridge that was seemingly there all along. These aspects were directly drawn from collaboration with Paul Fletcher, professor of Health Neuroscience at University of Cambridge, and a with frequent meetings with modern-day sufferers of both psychosis and voice-hearing.

The team has an excellent development diary about their research and motivations that is well worth checking out and Creative Director Tameem Antoniades has written several pieces on the role of mental illness in his design, including this one.

The tight focus on Senua herself, to the extent that she is the only character you see fully realised in the world, allows Ninja Theory to devote themselves to rendering her character with a degree of detail that makes her seem overtly human, especially thanks to the astonishing performance by Melina Juergens.

It also centres the player’s experience entirely on Senua creating a feeling of harrowing introspective isolation. The combination of this raw portrayal of Senua’s emotional turmoil with well-grounded research into scientific modern understanding and personal experiences of psychosis gives us a keen sense of her dislocation which serves to intensify the intimacy and immersion of the story and gameplay rather than distancing the player.

It also achieves another end, it renders the experience of mental illness in the past on a distinctly human and personal level. This is partly achieved through some satisfyingly sensitive attention to historical detail in her character design. Antoniades has said that he wanted to create a historical fantasy, and personally, in making Senua an eighth-century Pict from Orkney I feel he couldn’t have chosen a better place or period to give the team a considerable amount of leeway in their art direction.

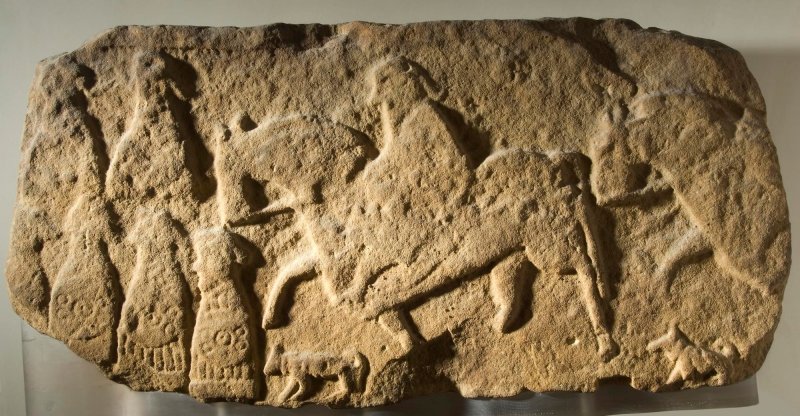

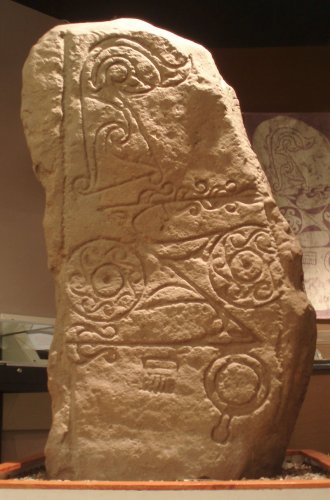

We know comparatively very little about the daily lives of the Picts and even less about the Picts of Orkney. The carved stones which litter North-Eastern Scotland as well as Roman, English, Welsh and Gaelic histories and poetry give an insight into a powerful kingdom with a rich culture. A few Pictish additions to the impressive prehistoric fortified brochs and settlements remain in Orkney but little else to give us an idea of how ordinary people lived and dressed.

It is generally accepted that the Orcadian Picts were eradicated by invading Norsemen in the ninth century as triumphantly detailed in the thirteenth-century Norse Orkneyinga Saga, and it’s difficult to make any other judgements about why they disappeared when so little documentary evidence of their culture survives (if you’re interested it’s worth checking out this site).

So Antoniades and his team have broadly grounded Senua in a pre-Christian Celtic context. She wears a typical Pictish brooch, a wolf skin, a stamped leather jerkin and a checked weave cloth which ties neatly into ideas about pre-modern tartans. They decided to give her dreaded hair inspired by Roman accounts of Celtic tribes using lime to lighten and clump their hair together, which is a reasonable artistic choice, especially when hairstyles so rarely survive in archaeological finds for this period.

I also like the very simple use of blue face-paint. It’s probably the one thing everyone thinks they know about the Picts but we have very little actual evidence of how it was worn or what it was made of. The name Picts was drawn from Roman sources by Victorian writers and is generally taken to mean ‘painted people’. The blue comes from accounts by Julius Caesar of English Celts who painted themselves the colour of the blue-green glass popular in Rome and is largely the root of an idea that the caustic plant woad was used for tattooing (my advice for anyone who’s curious about authentic Celtic materials would be to definitely NOT tattoo themselves with woad, see here).

One of my favourite parts of Senua’s design is the mirror she wears at her hip, which comes into the story on several occasions and into the gameplay as the focus metre for her special attacks. Antoniades has said that they wanted to include the polished iron mirror because archaeologists have suggested that druids may have used mirrors to connect with the ‘underworld’. The importance of water is very clear in a lot of iron-age settlements and religious sites across Britain, particularly in cases of ritual sacrifice like the Lindow Man, a bog body recovered from a marsh in Cheshire now housed in the British Museum. By the early modern period reflections in mirrors and still bodies of water had taken on an important role in folklore and witchcraft trials (see for example Stuart Clark, “Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Culture,” in Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, ed, Bengt Ankarloo and Stuart Clark (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 103).

The use of the mirror inside Senua’s reality is a fantastic grounding in period context. Mirrors were undoubtedly high-prestige symbols and could also have been used to connect with the supernatural. And the thing that got me really excited is that mirrors appear ALL OVER THE PLACE in Pictish stones, which archaeologists are still trying to decode the meaning of today.

The final detail which really hammers home Ninja Theory’s grounded contextual world-building is Senua’s attitude to the corporeal remains of her lover. There is a tired historical trope that people in previous centuries were surrounded by death all the time, so it didn’t affect them. Certainly, in many cases cultural attitudes to the physical remains of the dead have shifted.

One of the reasons for a Western cultural squeamishness towards dismembered body parts is potentially rooted in the Christian church’s requirement that the body be whole to get into heaven; the theory being that souls entered heaven during the apocalypse when Jesus would return and resurrect everyone from their graves, which, in a characteristically pragmatic style, medieval people thought would be difficult if you were in pieces (now executions which relied on quartering the body make more sense, right?).

Senua’s wearing of Dillion’s head is presented without drama in the game, she keeps his head for practical and emotional reasons, to keep him close as she tries to find his soul. The decision could have come across as grotesque and deepened the feeling of revelling in the physical horror of earlier ages, but its treated as such a natural action on Senua’s part that it chimes with the authenticity of Ninja Theory’s other contextual art choices.

Senua’s practicality with Dillion’s severed head makes the emotional impact of his tortured death at the hands of the invaders more significant. Rather than wringing its hands about how terrible things were in the past, the game instead shows the player how despite a different cultural context (i.e. being cool about her boyfriend’s severed head as a means of connecting to his soul) Senua is just as emotionally vulnerable to tragedy as people are today.

And this brings us back to the portrayal of her mental illness. It would have been easy for Ninja Theory to have made Senua’s psychosis purely a result of the horrific death of the only person who had loved her. But they didn’t. The darkness that threatens to consume Senua, has been with her since childhood. At many points in the game we get glimpses into Senua’s past, including her mother’s psychosis which resulted in her suicide as well as Senua’s father’s attempts to cure them both of the curse. Dillion is a brief moment of safety and kindness in Senua’s life and the cutscene where we experience Senua’s traumatic flashback to her discovery of his death is truly devastating. But her suffering before this event was caused by her mental illness, not the inherent cruelty of this one episode. And this is what makes Hellblade so powerful.

The tendency to make sufferers of mental illness in the past set-dressing or one-dimensional characters ‘mad because of the war’ deepens the disconnect between the experience of sufferers today and sufferers in the past. By making Senua’s psychosis and depression a thing she had always lived with, Hellbalde demythologises mental health in the past.

Not all mental illness is the result of trauma, and not all those who experienced traumatic events in the past were either driven mad by them or so inured to the emotional fallout that they were unaffected.

Placing the player in the active role of someone suffering from psychosis in a period of violence allows us to explore the personal experiences of historical mental illness beyond the typical ‘othering’ narrative that the mentally ill were objects to be dealt with, avoided or contained. Hellblade is sensitive to our modern understanding of psychosis but it’s also sensitive to Senua’s historical context in way which gives a tangible connection with what is extremely difficult to reconstruct from surviving records. It gives a voice to modern mental illness but it also gives a voice to the past.