In the first of three articles written about his time recently spent investigating the Toronto independent development scene, Ryan coordinates a meeting with one of the collective known as the Hand Eye Society.

In early August, 2015, I had the chance to travel to Toronto for the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, an organization I belong to due to my professional work and study being within the field of mental health services.

I was excited not only to travel the great distance and present my professional material, but also to explore Toronto’s legendary independent gaming scene.

I made time, while in the city, to sit down and talk with some of Toronto’s most talented and influential game designers and writers.

This, along with two other articles, chronicle the conversations I had and the demonstrations I experienced when plugging myself into this thriving community.

I hope it will be of use for those inspired to create games themselves or those looking to bolster their own local independent communities.

Among those who I reached out to for interviews, I was particularly interested in the Hand Eye Society; a collective of Toronto-area game developers founded by Raigan Burns and Mare Sheppard of Metanet (n++), Jon Mak of Queasy Games (Everyday Shooter, Sound Shapes), Jim McGinley of Big Pants (Endlight), Jim Munroe of No Media Kings (Unmanned), and Miguel Sternberg of Spooky Squid (They Bleed Pixels).

The Hand Eye Society promotes the artistic and cultural relevance of games. They hold socials, engage in many public-facing events, and engage in many fun and interesting projects.

Among the most famous of these are the Torontron arcade cabinets built by the group; old arcade cabinets gutted and retrofitted to house modern games from Toronto’s independent game scene.

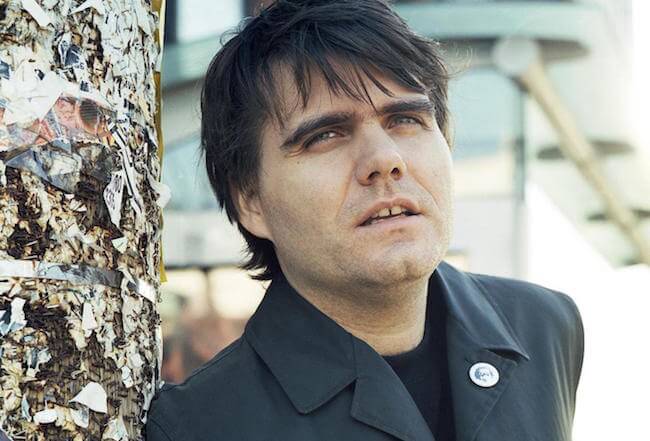

The first individual I met in Toronto was the esteemed writer (under the label No Media Kings) and founding member of Toronto’s Hand Eye Society, Jim Munroe. He had a curious and observant gaze that was evident from the minute he walked into the café / bar in which we met. He was very polite and welcoming, and he seemed to be able to tell that I was from Seattle from my accent — a curious talent I could not even begin to guess at. Drinking coffee and snacking on roasted almonds, we settled in and began talking about games.

Readers may be familiar with Jim’s name if they have followed some of the more notable text-based adventure games over the past few years. He has authored many award-winning and attention-grabbing games, such as Unmanned and Everybody Dies. Many of his games can be played freely.

Previously, he has worked as a science fiction author, graphic novelist, film director, radio dramatist, and journalist, among other roles. On top of all of that, Jim has served as an artist-in-residence at the Art Gallery of Ontario, where he created a game that plays like an interactive and humorous tour of the museum called A Playful Fiction.

Though he seemingly has more published and acclaimed credits than I have days in my life, he could not have been nicer in our meeting, and he was very excited to talk about his work and the exciting projects that the Hand Eye Society has been undertaking.

How does one, I was curious, “pitch” the idea of creating game art in-residence at the Art Gallery of Ontario?

Jim approached the AGO in hopes of using their space to hold an event celebrating local games art. He could not afford their asking price for use of their space, as his organization is not-for-profit and he did not have a budget for such things, but he did pique their interest.

The AGO, though a traditional art gallery in most respects, had a great interest in attracting the talent of less conventional artists, and exhibiting the work of a local games artist could attract some excellent publicity and audiences that may not otherwise venture into the museum.

The museum offered him a position as an artist-in-residence, for which he would be afforded a space to work and exhibit within the museum, and the public would have an opportunity to interact with him.

The museum had not garnered a lot of attention for their artists-in-residence in the past, but Jim drew a lot of public appeal and media coverage in his time at the AGO. Though the “are games art?” debate is quite over and settled among those within the games-space, it is surprisingly still being widely debated by those in the general public, and Jim’s exhibition was a very public way for the museum, right in the heart of Canada’s artistic scene, to say, “yes, Jim’s creations are important and worthy of being called ‘art’ in every sense of the word”.

In fact, the exhibition was successful in attracting a much younger audience than the museum typically brought in, and it managed to attract more non-members than any other exhibition that they have ever housed in the past.

This partnership with the AGO ultimately culminated in the Hand Eye Society Ball, a public social event corresponding with the fifth anniversary of the Hand Eye Society’s inception.

The party celebrated Toronto’s local videogames, with particular attention given to how much the community had grown during that time.

These types of retrospective events are important, Jim says, because of one particular weakness in game developer and player communities.

Gaming, as an artistic and commercial medium, has been growing, expanding, and innovating at a breakneck pace in the past thirty years, and it shows no signs of slowing down.

This is, in part, due to the culture of creators being very forward-thinking and excited about new ideas and new directions that they can move in. The games community is really open to things that are new, but, because of this, their memories are quite short.

Compare this to the novelist and publisher communities, communities to which Jim also belongs, who are risk-averse, unwilling to innovate, and have excessively long memories.

Being able to take a look back and draw inspiration from games that have been successful (or even those who have unsuccessfully stumbled over ideas too grand for their scope that could be revisited years later) is what truly creates communities with permanence and lasting power.

The AGO certainly took some risks in housing Jim, particularly within political spheres. Though Canada has wonderful endowment of the arts programs, government-supplemented grants for artists, videogames have been traditionally regarded as a commercial product and, thus, are well supported by the commercial sector.

The Hand Eye Society has been hard at work educating arts councils about the needs of independent creators and the ways in which endowment funds can be utilized to help game creators.

There are specific cultural factors at play in Canada at play. Many independent game creators label themselves as “new media” authors so that they can secure grants from endowment of the arts programs.

The system wants creators not to attract attention, lest right-wing newspapers write that the public’s money is being used to fund games, and isn’t that frivolous? This forces a lot of people to create boring and safe art. It allows them to continue creating art without endangering their funding.

One of the most striking themes in Jim’s game work is his desire to engage the general, non-gaming public. His residency with the AGO was one clear example of him introducing game art to non-gamers, and the work of the Hand Eye Society is predominantly public-facing.

Jim recounted that he played games throughout his teenage years, but fell out of touch with them as he got older until he was freshly reintroduced to them at a more advanced year.

He believes that a lot of people who have admired other types of art forms would find games compelling and wonderful, and he likes introducing it to people in a way that is not reliant upon having the advanced past-knowledge and lingo that tends to be present in gaming circles. He wants to give them a graduated ramp into the world of gaming.

Games can be exclusionary. Playing games often necessitates owning a gaming console, and those require large sums of money up front. Compared to the relative ease of acquiring and watching films, games can be an expensive and difficult hobby to get into.

In recent years, though, high quality games have been finding their ways into the public’s hands through devices that they already own.

Phones and tablets offers the public a portal to a wide array of easily-consumable, high-quality content, and pointing people towards “the good stuff” can be a fun an rewarding exercise.

Now that the barrier to finding and obtaining games has been significantly lowered, the last obstacle that Jim notes is that of game literacy.

Jim explains that traditional literacy is the ability to read and write, and game literacy is the ability to play and create games.

Separate from the dexterity and skill requirements of playing a game, true game literacy is being able to interpret the mechanics of a game and understand how those mechanics can inform (or undercut) the personal or written narrative of a game.

The way that a character moves and the way that the game world reacts to the actions of a player are fundamental in having a truly rich understanding of a game.

Unless you have the language for it, Jim explained, people tend to give games rather polar descriptions without much nuance. Game literacy is about noticing the tension between interactivity and narrative control.

That is, what the author “intended” and what the game allows by nature of being interactive. The two forces are oppositional and, from that tension, emerges the core of what makes videogames unique and effective as an art form.

To promote game literacy, the Hand Eye Society holds classes, in partnership with local libraries, schools, and recreation centers, called Game Curious that function much in the same way that a traditional book club would.

Over the course of 12 weeks, members of the public are encouraged to come by and improve their game literacy by engaging with and discussing a curated selection of videogames of all varieties.

The first six weeks of the Game Curious program are the Play sessions. Several computers or game systems are set up to be freely interacted with by the members of the public who attend, and the group gathers together to discuss their personal experiences with the games afterwards.

The conversation is facilitated by volunteers from the Hand Eye Society, who will ask questions and follow-up on pertinent points in order to give the attendees the language with which to discuss games.

Over time, the attendees begin to draw links between the themes of the games on display, connect their personal experiences of each of the titles, and tap into the richer narrative that, otherwise, would have been invisible to them.

The latter half of the Game Curious program is comprised of Make sessions. These sessions give attendees the tools and training to create their own games.

Through the use of simple programs and with the top-tier assistance from the Hand Eye Society volunteers, attendees are encouraged to explore their imaginations and express themselves through the creation of a game of their own that they can share with the other group members.

Jim believes that making games is like writing, and it is integral in game literacy. For those who lack the technical skills or desire to program, Jim recommends still being involved in the creation of games to some degree.

Promoting games, curating games, and marketing games are still essential steps in the creative process, and they often go overlooked. Connecting with independent communities and offering those kinds of services is always appreciated.

The indie community pushes everyone to create games from scratch, which is a great thing, but it can also be exclusionary to those without the training. The Hand Eye Society offers services for connecting HES members and the public when one or the other has needs.

They have a program called Beta Buddies, in which people can sign up to beta test independent games. This benefits the indie developers immensely by giving them a pool of eager testers of a wide array of backgrounds and play experience levels, and it also benefits the public by allowing those interested to have a way to contribute to exciting new games.

In that way, the Hand Eye Society acts as a gateway between the public and the independent (and even industry) communities, allowing passage and communication in ways that would have been impossible otherwise.

The Hand Eye Society also makes a point of boosting interesting games and ideas. Several local games have made their first public appearances at Hand Eye Society socials, most notably Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP and Nidhogg. The Society also hosts annual showcases called WordPlay, events that showcase some of the best-written games. The event showcases about 20 games each year and invites a number of speakers to give talks and panels about their work.

Speakers in the past have included Cardboard Computer (Kentucky Route Zero), Emily Short (Counterfeit Monkey), Sam Barlow (Her Story), the Night in the Woods team, Sherwin Tija, and Christine Love (Analogue: A Hate Story) among others. The WordPlay events are free to the public, and many of the panels can be watched on the Society’s website (http://handeyesociety.com/wordplay/).

Though well-established by this point, the Hand Eye Society provides a surprisingly tenable model for game development communities looking to expand their focus or become more public-facing. Individual projects are sometimes funded by individual sponsors, arts councils, small grants, and partnerships with the Toronto Independent Film Festival.

For those wishing to follow its model, funding can often be secured for programs like Game Curious, as they offer technical skills and community literacy programs to underserved neighborhoods.

Public libraries and recreation centers will often be excited to host such events, as both have community outreach and activity budgets and are always looking for new ways to attract people to their locations.

The Hand Eye Society does not have membership fees, but it does suggest that all members contribute ten hours of volunteer service to the Society each year. This gives them the workforce that they need to staff their Game Curious, Torontron, and WordPlay events, and it keeps the community actively involved in the workings of the Society.

Jim has an advantage of being an arts organizer for over 20 years, but he recommends connecting with communities working in different media art mediums. Those connections can prove to be invaluable when it comes to sharing knowledge, contracting help for innovative projects, and keeping ideas and perspectives fresh.

The more that the arts can cross-fertilize, the better they will be. Also, connect with art galleries, artistic organizations, studios, and experimental filmmakers. These can all be excellent resources for boosting a community’s visibility.

Look for the needs of the public community in which you live. Find ways in which showing off your games can fulfil a deficit that the public is already feeling. Finally, show unexpected games in unexpected places.

Jim has had great success in going out into the community and projecting games onto the sides of buildings, allowing passersby to play in public. He also has enjoyed curating games for concerts and galleries.

Being able to “sell” your services to these types of venues as being beneficial to them will land you opportunities and contacts you may not otherwise have.

Lastly, Jim implores creators to never be afraid of using the word “game”. It drives him crazy when people talk about “interactive art” or “new media” to avoid the term “game” which some people see as frivolous.

He likens it to how Margaret Atwood would distance her writing from the (pulpy by reputation) science-fiction genre by calling her works “speculative fiction”.

Ultimately, what inspired Jim was not just interactive art – Jim was inspired by games. He asks people to address their cultural elitism and recognize that there is still magnificent, enjoyable work being done in the “cultural gutters”. If you’re willing to call yourself a creator of games, you are not a pretentious person. It requires a great solidity of character to stand up to opposition.

The Hand Eye Society website displays a quote from Brandon Boyer, the Independent Games Festival chairman, that I think really encapsulates what makes their work so compelling. He implores Toronto to “[make] games a part of civic pride”. The Hand Eye Society is proud of the games that have come out of Toronto, and through the collaboration that the Society empowers, they are enriching future Torontonian game as well as educating and serving their local community.

More and more each year, the public is being made aware of the fantastic artistic work that is being done in the lofts, basements, and offices of their city, and Torontonian games are truly becoming a part of civic pride.