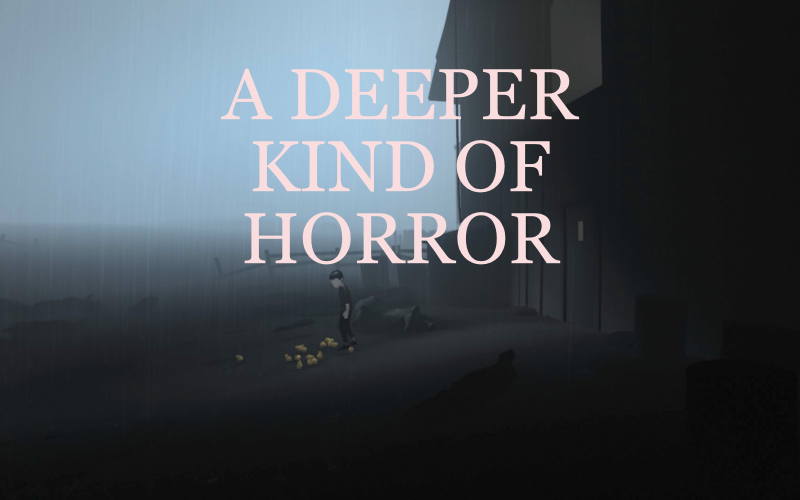

The first level of the game INSIDE is a terrifying gauntlet of masked men, dogs, and dark woods.

A half dozen narrow escapes and near-death experiences later, the game suddenly shifts gears. The second level starts not with violence or fear, but with a dozen chicks following the protagonist around like he’s their mother hen. They chirp encouragingly and served no apparent purpose, other than a bit of unexpected companionship in the game’s lonely world.

After a cornfield and a muddy pasture, the chicks and I made our way into a barn together and were seemingly blocked from any progress. All the barn contained was a few hay bales and a mysterious machine: a machine built to suck in and churn out anything small enough to wander past it.

The chicks, apparently, served a purpose after all.

INSIDE is full of moments like this – initial confusion followed by the stomach-turning realization of what the game expects. It establishes dread.

Everyone has seen a horror movie with a “Don’t go in there!” scene, like the attic in Paranormal Activity or the basement in The Evil Dead, in which a character makes an ill-conceived and horrifying choice and pays the price for it. The tensest moments of those movies are in the approach, the careful creep down the stairs before discovering what monstrosity awaits.

Over and over, INSIDE confronts the player with a series of “Don’t go in there!” moments. Unlike its movie counterparts, INSIDE never let me agonize while a third party did all the uncomfortable stuff. The game made me responsible.

I had to turn on that machine to suck in the chicks, and I had to pull a parasite out of a horrible squealing pig, and I had to dive into the deep dark water even though I knew something awful lurked below.

INSIDE only rarely pressured me into action. It allowed me to linger, staring uncomfortably at the screen and wondering if there was any way around what the game wanted. It has one jump scare, maybe two; it doesn’t traffic in shock. Playdead, the developer of the game, instead harnessed apprehension and anxiety to make truly unsettling gameplay without many of the horror genre’s usual tricks.

Fear in INSIDE is a crawling angst, an unnerving drip of images and sounds that broke down my mental barriers and wriggled under my skin. Playdead isn’t new to this either. They’ve been doing it for years.

There’s a moment in their 2010 game LIMBO when the spider that’s been chasing the player for most of the game emerges one final time, dying and missing most of its legs.

It makes a few weak jabs and then collapses. Even while dead though, the spider blocks the way forward. There is no way back and no way over. The only way to progress is to approach the giant dead beast and pull its remaining limb, pull until the skin and sinew connecting it to the body snap, and push its oblong body until it forms a soft bridge across a pit of spikes.

It’s sickening. I would have covered my eyes if my hands didn’t have to stay on my controller. And yet, the most powerful part of the experience wasn’t the detail in the spider’s dismemberment, or rolling its body across the ground. It was the moment I realized I would have to approach (and touch!) the dead spider if I wanted to progress.

The best example I’ve experienced of this ilk of preliminary dread came not from INSIDE or LIMBO, but a tiny itch.io game called Anatomy (previously written about for Cane and Rinse by Alex Maskill).

Anatomy’s only gameplay is walking around a dark house, finding cassette tapes, and returning to the kitchen to play them. Each audio recording details the way a room of the house resembles a part of the human body: the living room, a heart; the bedroom, an unconscious mind; etc. Anatomy gives each room an uncomfortably organic, almost sentient character before asking you to delve into that room and find the next tape. It’s a game built on apprehension, the same kind I feel when I look out a window at night and half expect to see someone looking back.

After listening to them over and over, the tapes in Anatomy start to degrade. The stable monotone of the unknown lecturer turns to static. Tapes hitch and skip, and others occasionally increase or decrease their volume wildly. Late in the game, one snaps. The lecturer’s voice gets louder and louder until it’s suddenly replaced by a woman’s voice, high and cold and somehow speaking directly into the player’s ear.

I look out of the bedroom window and I see a truck approaching. A young man steps out, approaches, and enters through the front door. His body is covered in swollen ticks the size of quarters. He’s walking through the downstairs hallway and laughing… He’s moving through the first floor, breaking and upsetting things. He goes to the basement and stands at the top of the stairs.

I’m angry at him, so I slam the door. He falls down. I can feel his bones snapping. The ticks are bursting, oozing cold black blood everywhere. I can feel him being ground up, dissolved and torn, splitting and shredding. I leave the door closed. I close my eyes and try to sleep.

The entire layout of the house has been built for this one moment in Anatomy. The tape recorder sits on a table in the kitchen, and the kitchen sits at the end of a long, dark hallway. There’s no way to see down this hallway while the tape is playing, and so instead I stood in the kitchen, chills running up my arms and down my body as the woman in the tape whispered about this horrible man walking directly towards me.

He didn’t come.

Instead, as she continued to speak, I forced myself to turn to the one other door in the kitchen, the one the game kept locked throughout the entire playthrough. When she finished, leaving me to imagine whatever horrible thing lay below the house, that door swung open. The door to the basement welcomed me in, and my only option was to follow it down.

More of Jacob Geller’s work can be found on his blog at thirteenthcolossus.wordpress.com, or on his twitter @yacobg42