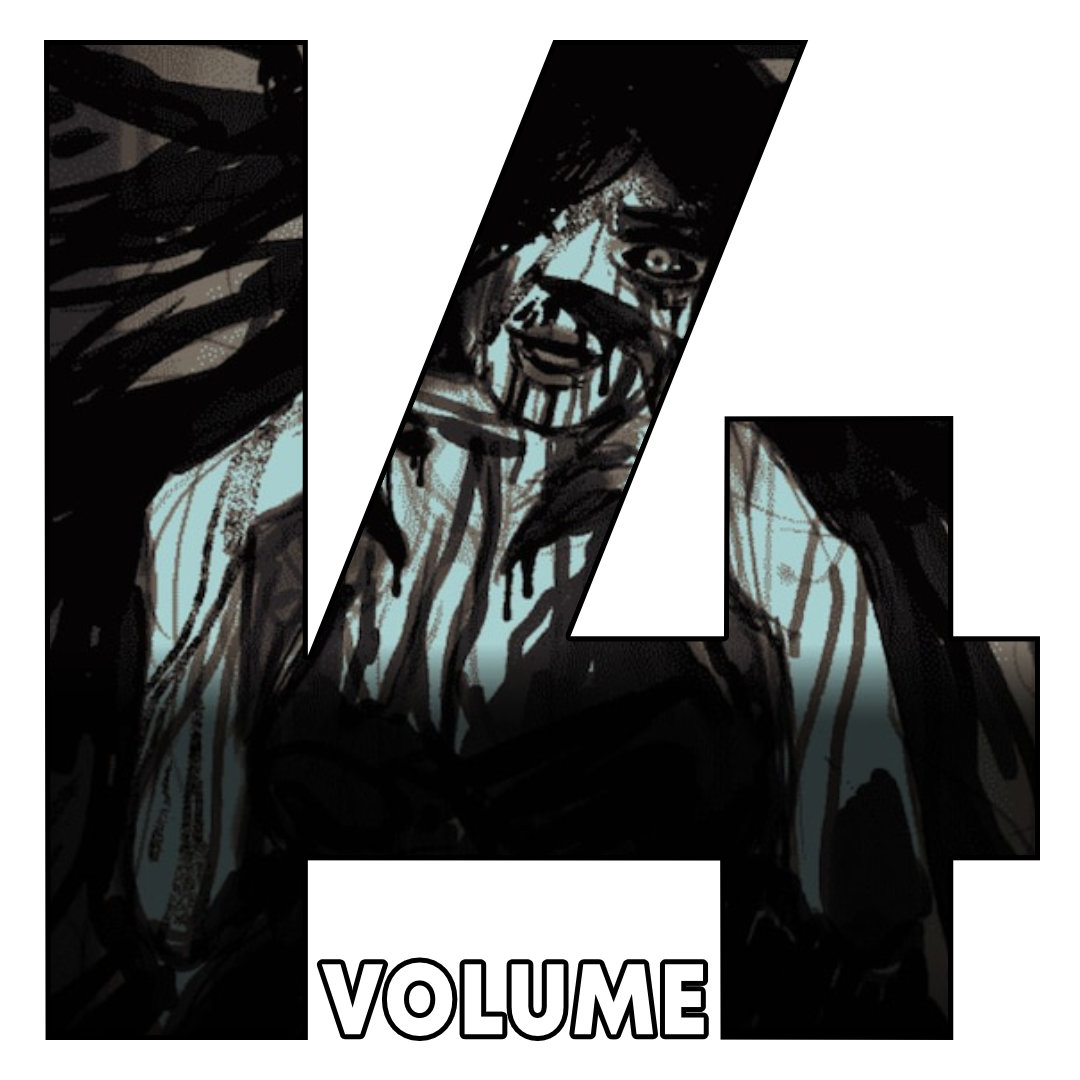

Two origami snakes weave their way through a dense forest of paper trees towards me with a hiss. A single touch from either means death.

I whip around and loose bolts of flame at them. Tie. Ego. They sizzle and parch as they burn, but their places are immediately taken by great, hulking larvae and what appear to be huge, intricately folded tarantulas.

From the opposite direction, two more snakes appear. I’m surrounded, fixed in place among a ring of floating rocks that glint and glow as I work.

I quickly burn the snakes – cry, lip – but the larvae and tarantulas have already gained ground. I target the larvae with bolts of electricity, short bursts of ruff, fend, debt and flee, and as the shocks wear down their many weak defences, the electricity jumps to the tarantulas, indirectly shattering their relatively intimidating backhands and joysticks.

An icy incompatibility freezes what appears to be a gigantic paper botfly as I tour and huge and urge more sparks at a mob of gangling spiders.

They’re close to death now, each with just one word left – but there’s too many of them, sparks don’t jump on an enemy’s last word, and there’s nothing newer and healthier to serve as a conductor.

I clatter out their final words in a frenzy, gusts of wind keeping other solitary enemies at bay as I work. Finally, the botfly snaps free from the ice and I loose flames at him, each hit slowly burning away the word behind it as well. The flames engulf the botfly, and it dies.

Epistory: Typing Chronicles, or The Typing of Okami as it’s come to be known in my head, is at its best when it marries its love of language with its snappy, tactile core gameplay loop of running, typing and switching between elemental forces.

It’s an action-adventure typing game from Belgian developers Fishing Cactus, with the structure of a Zelda game.

Your character – an origami woman sat on the back of a huge three-tailed paper fox – makes her way around an over-world and eight themed dungeons, each with their own distinct puzzle mechanic.

The twist is that your character interacts with the world with magic, activated by the player typing out a matching word (or letter, or set of nonsense letters, or even the occasional number) on your keyboard. A completed word might be a treasure chest snapping open, or a barrier collapsing, or a bolt of energy launched at a monster.

The brilliant part is that when words, our most abstract, instinctive units of communication, are the main way you interact with the world, it weaves rich communication with that world into the very fabric of play.

When you’re in a burning volcanic trench, working your way around with deliciously flammable words, or sending sparks of voltmeter and charge around a long-abandoned factory, the gist of the environment and tone is relayed constantly through the tasks the game asks of you, without you even necessarily realising it. The words a level uses both reinforce it and allow you to exert control over it.

I found myself, halfway through a level, suddenly noticing how totally convinced of the setting I was, purely because I’d internalised a constant stream of description of what the environment was like through the gameplay. The game’s no slouch in the traditional departments; its gorgeous aesthetic – all colourful paper characters and environments, evoking the painterly quality of Braid and Okami and the origami look of Tearaway – and sharp sound design excel at creating a tangible world on their own.

However, this extra layer of communication adds so much that even a conversion to more traditional action adventure mechanics, within the exact same game. would fail to convince or charm in quite the same way.

In combat, this system becomes entirely different. The player is typically fixed in place when encountering anything more than one or two creepy-crawlies, and each enemy has a set of words to be worked through one by one, before they die.

They spill in from every direction, and if one of them touches you, it’s game over. Here, the words are less descriptors than they are magic spells, spat out by your witch player character as she fights back the primal forces of nature.

Differences in length and number of words combine to create enemies that feel palpably different to confront. So to do the effects of the four elements your words can take on as you proceed through the game.

Fire potentially doubles your attack power, if you have the time to let it burn away at the enemy; ice, by comparison, buys you a handful of precious seconds, but hits for one word at a time. Spark can potentially shock many enemies at once, but is better for softening crowds up than it is for finishing anyone off; wind lets you control the combat space by pushing enemies back with powerful gusts, but can push them out of attack range.

Combat is both tactical and tactile. It combines the quick analysis of the oncoming mob of enemies for the best possible mode of attack with panicked sputters of keyboard presses as you try to get the attack out before they gain too much ground. Different foes in different combinations all demand both a thoughtful, strategic response and the dexterity to be able to pull it off in time. If you aren’t a particularly skilled typist going into this game, you’ll have to step your game up pretty quickly in order to keep up.

There is an extent to which the game tapers off in its tail end; unlike a Legend of Zelda game, you rarely take the mechanics of one dungeon with you to interact with the systems in another, and when you do, it’s usually just as a mechanism for opening doors.

Likewise, the combat encounters never change or build upon one another meaningfully, offering a range of differences of scale but few differences of kind. You’re given new ways to overcome the core combat puzzle, but it is always the same puzzle – waves of small enemies and the occasional large enemy, all of which are beaten by typing the same sorts of words.

Properly expanding mechanics are expensive, and ultimately Epistory is a self-published independent production through and through, constrained by its own forcibly limited scope. It changes enough to not feel too repetitive, but also never feels as developed as its early successes promise.

Similarly, the final dungeon feels like just another elemental dungeon until you’re suddenly confronted with the game’s conclusion. This would have been another great opportunity for a difference in kind, where a switch-up could have given the game’s ending a real sense of escalation.

Instead, it peters out, finding a thematically satisfying but ludologically underwhelming conclusion.

However, these flaws cannot snuff out the game’s charms: it’s still gorgeous; it still has that snappy, frenetic and tactical combat; and it uses language in a manner I’ve never seen before in a videogame, one which grants it a rare richness and wit.

If I were a numerical ratings man, I’d have to call it a ‘seven’ with the beating heart of a ‘nine’. As it is, I’m happy settle for it being smart, inventive and deeply charming.

(Disclaimer: I semi-frequently hang out with the writer of this game, so I won’t comment on the story too much except to say that I found it to be unobtrusive, charming and effective.)