Jon Cheetham followed the trails of Sekiro and gained a deeper appreciation for the depth of From Software’s magical realism Sengoku masterpiece

NB: Major story spoilers for Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice follow

From Software’s challenging, GOTY-winning Shinobi action game Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice is gorgeous. That goes without saying, given From’s impeccable reputation for crafting considered, detailed game worlds. It is also a lovingly crafted journey through Japanese landmarks, history and culture. Many games evoke the aesthetic of uniquely beautiful Japanese art styles and architecture – Sekiro goes further, recalling the country’s heritage.

A journey through Ashina will familiarise the player with sights and buildings from many parts of the country, and my travels in Japan have brought home just how widely the game’s designers looked to find the perfect inspirations for the game. It is fascinating to ponder what the team might have been thinking when they included real places and cultural aspects in the game. I would like to say at the outset that I don’t wish to project intention onto the game’s developers, nor do I want any of my feelings about these places to come across as conclusive or instructive. Neither am I Japanese, and as such there will be many things I fail to properly understand. This is simply an expression of excitement, appreciation and speculation as to the real world references found in Sekiro.

There were some places I recognised first time through the game, as I had been there before Sekiro’s release in March 2019.

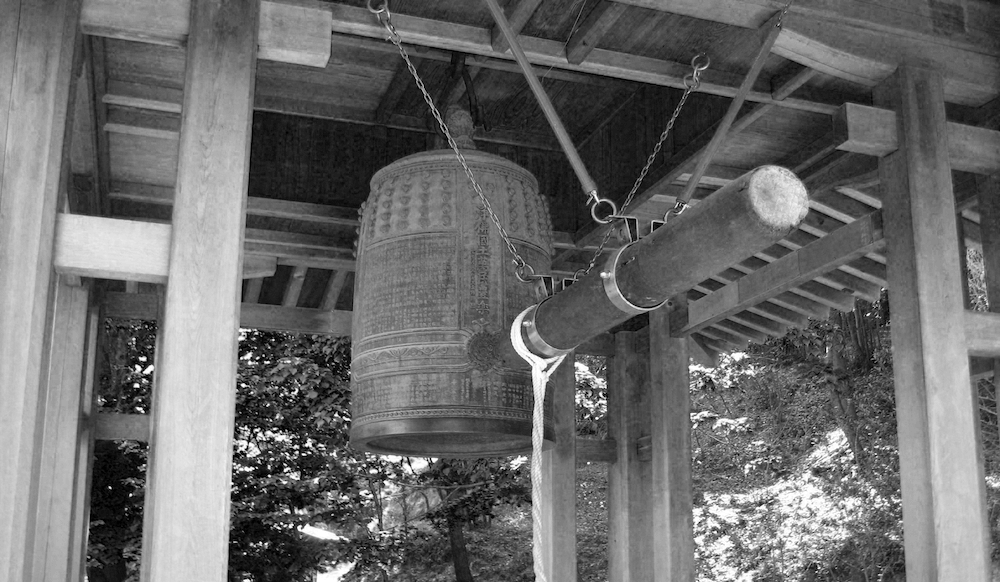

The bell at Mount Shosha for example, which you can ring on the path up to the temple called Engyo-ji. This temple is most well known for being the site where scenes from The Last Samurai were shot, but in Sekiro this bell (and others like it at Kyoto’s Kiyumizu-dera and other places) resembles the infamous Demon Bell found by bypassing the headless kappa-like creature that was once Ako and emerging at Mount Kongo. Ringing the bell makes the game harder – like other visitors, I had rung this bell to pray for world peace before ascending the trail to the temple. The immense sound of these giant bells or bonshou was believed to carry to the underworld itself, which makes sense when you check your inventory after ringing it and see that Wolf now carries the Bell Demon with him.

There’s the incredibly scenic walk through Arashiyama in Kyoto, bamboo groves on all sides. Even throngs of tourists couldn’t dispel the mystical atmosphere of this place; the tranquil green that surrounded us made me feel as if I were in a dream. Appropriate, as this environment is recalled at the Dragonsprint and the Hirata Estate, which Wolf walks through in the game’s dream sequences. Having been there and seen how unique and precious a place this is, I can see why the designers might feel that the burning of these groves and the settlement within would feel appropriately sacrilegious as the backdrop for the kidnapping of the Divine Child.

The tour of Japan continues when Wolf reaches the Mibu Village. Here he finds villagers and labourers who have contracted a terrible plague, goaded as they were to drink a sake provided by the village’s nefarious head priest. The sake made them mad with thirst, and they drank the rejuvenating waters that serve as Ashina’s source of supernatural power, and the reason so many factions are hellbent on controlling the nation. This is what now afflicts them, far below the notice of Ashina’s ruling clan and military class. Mibu Village is a sunken, soggy place, partially submerged, perhaps representing the way the waters have claimed it. Its structures, however, are recognisable as gassho houses. A famous place for gassho houses is Shirakawa-go, in Gifu prefecture a day trip away from the city of Kanazawa. Shirakawa-go is also a very wet place, or it was when we visited, as it has rice fields that are necessarily submerged in water. Perhaps this is why it seemed a natural fit for an in-game location where the waters would have a more sinister role.

Oh, and the trees in Shirakawa-go grow persimmons – which Wolf can also find in his journey through Ashina.

Ashina Castle, the most important location in Sekiro, recalls castles including those at Osaka and Himeji. Walking around those castles certainly gave me a new respect for how well fortified the daimyo would have been. These castles aren’t just incredible to behold – they are ingeniously well designed to repel invading forces. After our winding ascent through formidable, almost brutalist battlements and into the tight and defensible climbs of the interior, I could see why an assault on a castle occurred as the central endeavour of the game’s first half.

What really gave me pause though was reaching the top of Himeji Castle and looking out. Stunning is too mild a word for the view. The castle commands an almighty vista, taking in Hyougo Prefecture. I live on the 15th floor of a building, I work on the 20th floor of another. Looking down from miles in the sky isn’t unusual for a lot of city-dwellers now – but Himeji Castle was built in the 14th century. It is situated perfectly for the maximum elevation, and from its top floor one would see more than anyone else in the entire region. Even now, it has a view on all sides that no skyscraper I have been in can boast.

So I think about Genichiro, looking out from the rooftop of Ashina Castle. Being there doesn’t just make him the most well-protected person in the nation of Ashina, it means he and his generals have a powerful form of information access and control nobody on the ground level does.

Fittingly, having driven Genichiro off and won the highest point, Sekiro’s own eyes are opened to many things. Emma’s skills with a blade, Kuro’s true intentions, and private conversations with Isshin Ashina himself. I don’t know if it was intentional, but it seems rather elegant that the game should open up the way it does once Wolf is able to stand at the place in the country that sees more than any other.

It really is amazing to consider these things more closely, now that I have a digital rendering of the Sengoku to run and grapple around in. Returning to Japan knowing the game so well, I tried to imagine where the developers took their visual cues from.

Some things are very direct references – the three monkeys from the adage see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil; Mizaru, Mikazaru and Mazaru. They are encountered (along with a fourth monkey, who rings a gong) as one of the game’s weirder boss fights. It’s a good pull and something people from many parts of the world will recognise and appreciate.

The aspect of this shrine I find more mind-blowing is the fact that Tokugawa Ieyasu is buried here. It is quite something to walk round the tomb of such a key figure in history – and an engraving nearby states that the Sengoku was interred here by Tokugawa. A century of bloodshed and furious battle was symbolically laid to rest here by the man who had a leading role in ending it. Weirdly enough, this ties in with one of my pet theories about Sekiro.

Wolf’s time at Ashina Castle and his rescue of Kuro leaves the defiant nation’s defenses in ruin behind him – from the mighty general Gyoubu, to the blazing bull and the ogres created by Doujun, as well as many of the other senior military personnel, rank and file soldiers and samurai. Along with Isshin’s death, succumbing to his long illness, this leaves Ashina vulnerable to the long-awaited invasion by the Interior Ministry. The latter is Daifu in the Japanese text for the game, or Prefectural Government. The Tokugawa Shogunate’s system of government was run via a sophisticated heirarchy of senior officials overseeing different parts of the country, as well as the religious institutions and fiefdoms of Japan. I have wondered, although it is not confirmed anywhere that this is the Shogunate of the era, if we as Wolf are not in fact doing Tokugawa Ieyasu’s work for him in weakening the Ashina and defeating their leader.

The Folding Screen Monkeys must be overcome to access the Mortal Blade which Wolf needs for his mission. I have neither the historical context nor the cultural knowledge to draw much of an educated conclusion. However it is fascinating to me that these very clear pulls from Japanese folklore are between you and the sword with which you will prevent Genichiro from holding off the Interior Ministry, and in real life are revered at the same site as Tokugawa Ieyasu.

A possible connection to the game’s lore was found elsewhere as well. One of the most striking places, and one that anyone who has played the game would be likely to recognise immediately, is Kumano Nachi-Taisha. This is Senpou Temple. Not only was I standing in a mountain range surrounded by forested slopes as far as I could see, but a red three-story pagoda evokes the colour palette of the region. On a baking hot day in June, I stood and looked at the mountains and listened to songs by Yuka Kitamura from the soundtrack, like ‘Senpou Temple, Mount Kongo’ and ‘Seekers’.

I had been looking forward to seeing all of this. But to my surprise, that wasn’t even the most amazing part about visiting Kumano Nachi-Taisha.

The rejuvenating waters are there. And you can drink them.

Before you enter Nachi Waterfall, you can pay an additional 100 yen to take a shallow bowl and drink from the waterfall. It is believed that this water has curative properties and will help you have a long life. While it is a far cry from the corrupting waters of Ashina, that lend inhuman vitality to those who drink from it, I was blown away by suddenly finding myself drinking rejuvenating waters.

The thing that connected with me most strongly though wasn’t a place – it was a piece of Shinto culture, that gave me new insight into a character from the game. The day after Boxing Day 2019 we went to Furumine Jinja, a Tengu-dedicated shrine in the mountains of Tochigi Prefecture. Wolf first meets the Tengu of Ashina near the site of his battle against the stentorian Gyoubu Masataka Oniwa. Later on, players will notice that the Tengu mask and costume are “hidden” in Isshin’s room after the encounter with Genichiro at the castle.

In my visit to Furumine Jinja I gained more of an appreciation for Isshin as a guardian of his land. Shrines are erected to Tengu because they are believed to safeguard the mountain and the surrounding area.

Putting aside how comically obvious the placement of the costume is, this reveals a lot about Isshin’s character. We’ve heard of a fearsome warlord, who forged an independent nation in the crucible of a brutal coup, and even now holds the Interior Ministry at bay largely with his reputation. Moreover, in one of my favourite lines by Isshin, he says to Emma (speaking in third person of the Tengu) “he can only swing the blade a few more times… and when that happens, the Tengu will be no more.” This really stuck with me because it shows how prominently battle figures in Isshin’s life – not only does he take it upon himself to personally fend off would-be intruders and spies, he literally quantifies his remaining time among the living with sword strokes as a unit.

Interestingly, you can find quite a bit of content online about how the image of the Tengu has changed from the spiritual perspective of Japanese people. They are Yokai who were bringers of war in the Chinese folklore from which they originate. The kind at Furumine Jinja is a Daitengu, which features the same imposing, elongated nose and flush red skin as Isshin’s mask. These are traditionally war bringers, and yet their image has softened to watchful mountain spirits today.

As we stood outside the shrine snow started to fall, and the shrine felt very peaceful. There was barely anyone else there. I don’t know if Isshin would have been content had Ashina been left alone – the sword techniques in the game speak of his obsessive pursuit of ever higher forms of swordsmanship, so perhaps he was always a warlike man. But if the writers of the game were thinking of the country’s unforgettable Tengu shrines when creating the character, it lends Isshin more of a protective element to his character than I had recognised before.

From Software’s approach to dense environmental storytelling is fascinating when it is applied to real-life locations and cultures, even if those are presented in a magical realism setting. You can read and listen to some extremely knowledgeable people who have gone into incredible depth with the lore of Dark Souls and Bloodborne, some of whom have even drawn parallels to Japanese mythology and spiritual tradition like Richard Pilbeam from the Sinclair Lore podcast series. And now, the breadcrumbs Miyazaki Hidetaka and his amazing team have left in one of their masterworks lead to real world locations and folklore.

Just want to say that this was a blast to read.

The story and lore in Sekiro is excellent, and your observations are a great addition to that lore.

Thank you for writing this.

Hey Kaneda18, thank you for the kind words, really appreciated! I’m glad you liked the piece.

This was really well-written! It’s clear you have a robust understanding of the lore of Sekiro, and the way you linked it to historical Japan was very thoughtful. What a great read!