Warning: Spoiler spores have completely infected this article and turned it into a big spoilery fungus. Do not read this before finishing the game!

The Last of Us Part II is a game that knows exactly what your relationship to this medium is, and will take advantage of that relationship to elicit the emotional responses it wants from you, and to further its themes. How you engage with and make assumptions about the ‘rules’ of playing videogames will in fact be turned against you throughout the campaign. At several points in my first playthrough of the game I found myself acutely aware of the designers looking at me and deliberately pushing for a reaction, often in quite specific ways.

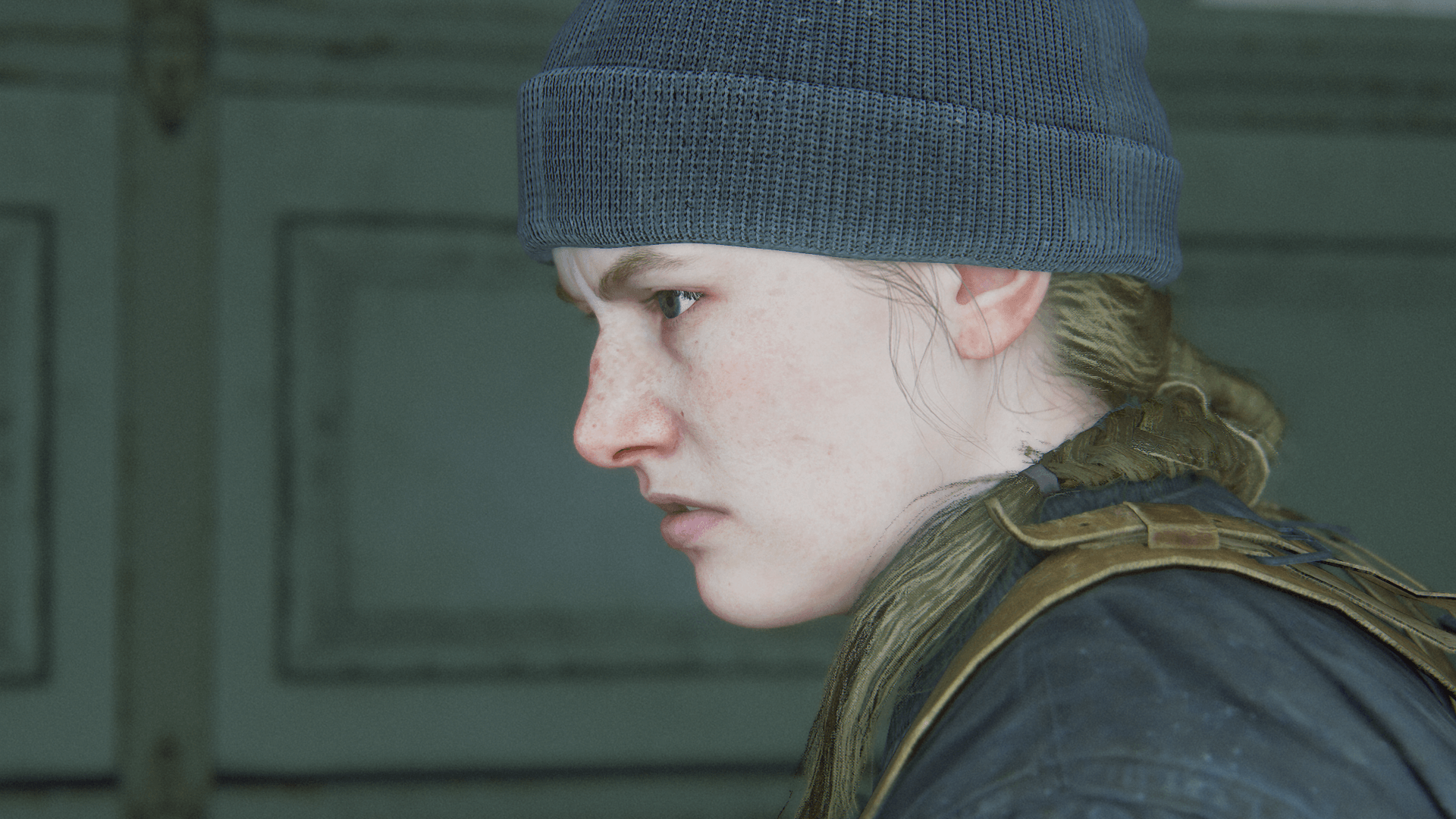

The game uses this in service of its broader themes – you have to push the player avatar toward hurting characters you might know and like. You hit button prompts to kill dogs and innocents. This first manifests in the opening hour or so, when all of a sudden you find yourself controlling a character who is at first unidentified. She’s armed and clearly as capable as any of Jackson’s protectors, and as the camera falls behind her you start pushing forward on the stick.

Eventually she is revealed to be Abby – and this is the person who is going to kill Joel Miller, the person you spent the majority of the original game playing as. But because this is a game, you can control someone whose motivations and inner life you have no idea about – an opportunity for cohesion with the story’s themes the developers latch onto. Like me, you might then carry on into Ellie’s section of the game assuming that the central tension of her emotional journey will be that she is avenging a father figure whose actions on her behalf she is ignorant of – until later on you discover that no, actually Ellie did know. Again, the player is distanced from the avatar with this demonstration of knowledge dissonance.

Usually I know what my avatar wants – Geralt wants to find Ciri (and save the world), Aloy wants to learn the truth (and save the world), my Skyrim guy wants to collect all the cheese wheels. This time I realised I hadn’t fully understood why Ellie was so hellbent on murder and vengeance.

But you’re going to play the game, and play you do, driving Ellie through one horrendous decision after another and usually not really knowing why. And those bad decisions are many. Leaving the (it turns out) extremely vulnerable Dina unprotected two nights in a row in an abandoned theatre in a city convulsed by civil war and still infested by flesh-hungry mutants. Splitting up from Jesse when he sets out to find Tommy. Killing Mel. None of these things are really defensible in the way Joel’s choice was, or Abby’s.

On the other hand, Abby’s campaign finds you embarking on quests and exploits much more how you normally would in a videogame – you wake among friends, stumble from one set-piece to another, get into scrapes, get rescued, then rescue a boy and his big sister, try to protect these kids against the odds and have some boss fights. When Abby’s story catches up to Ellie’s and we get back to the critical moment at the theatre, the player has been on a hell of an adventure. The inputs and button pushes you had to make to progress the horror and trauma of Ellie’s campaign have been applied to more positive verbs, like rescue, save, overcome – as opposed to murder, torture, abandon. I walked away from Dina, but I walked toward and alongside Yara and Lev over and over.

Videogames depend on reward systems, and one of the non-mechanical rewards can be a message that you saved the world, or rescued someone, or became the chosen one – basically that you did A Good Thing.

That reward is withheld throughout The Last of Us Part II’s downcast first half, but if you can just accept the fact that you’re now controlling the person who killed Joel, all those positive associations are free to fire in the back half. After an emotionally miserable opening act, the game has now established this new character as a fairly classic videogame or action movie hero. Abby even fights her way out of an infested skyscraper, in a sequence that is like Die Hard with fungus. What’s more, she has become Joel, a gruff protector, with the outcast Seraphite boy Lev as her Ellie. Soon after meeting the outcast kids, you even run to safety cradling Yara much as you did as Joel with Ellie.

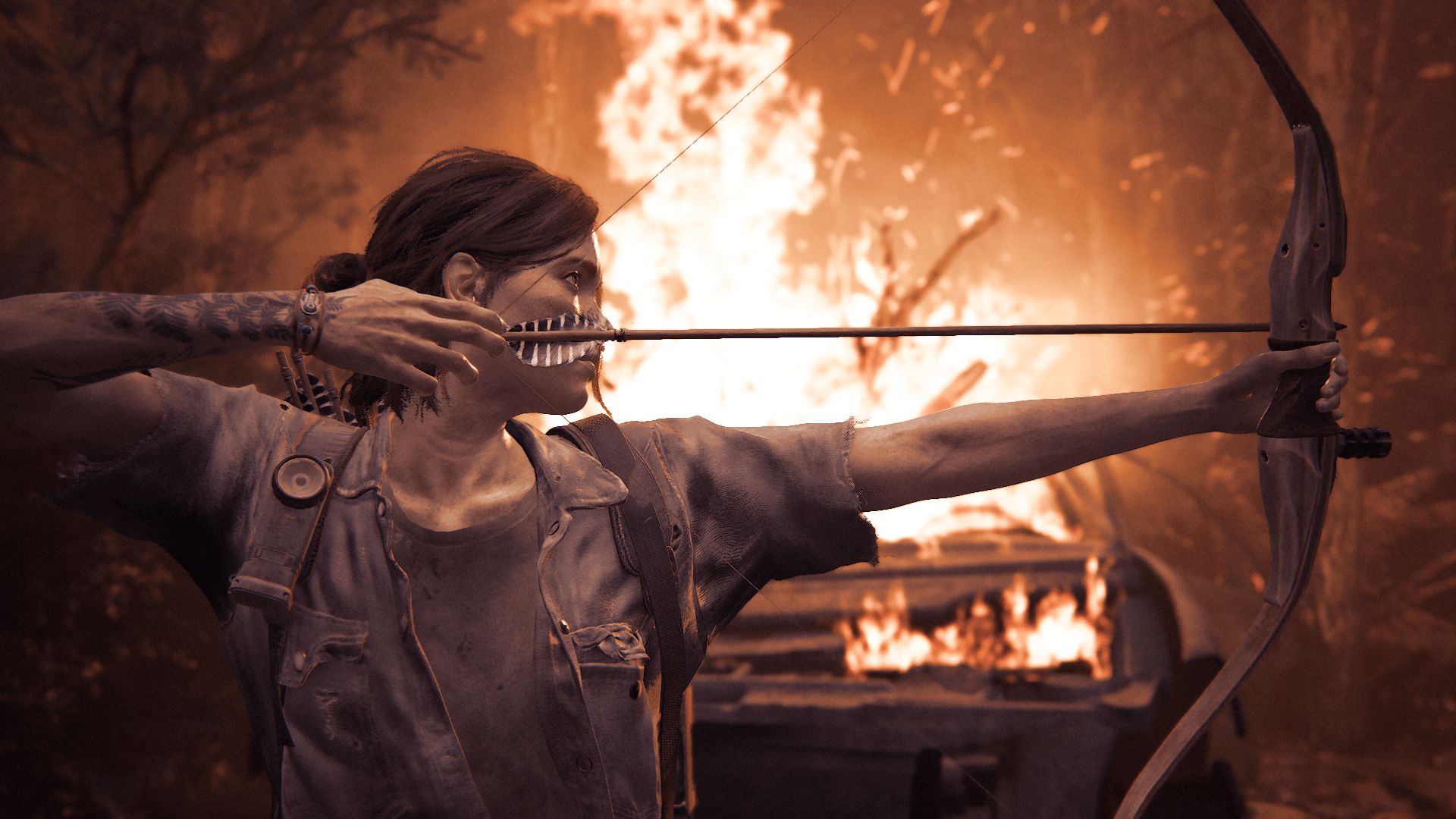

While some might see the climax as leading up to the confrontation with Abby, I now see it as leading up to Ellie accidentally saving her. I didn’t want Ellie to go to Santa Barbera on the terms she did – abandonment of those who love her yet again – but because it was another chapter of this amazing game I could play, I obviously went with it. Lucky I did – lucky she did, in a way. Although Ellie’s decision to leave her girlfriend and child and continue her quest for vengeance at Tommy’s embittered goading is unforgivable, it does mean that Abby and Lev are saved from the Rattlers when they otherwise would die. As it happens, whether you control Ellie or Abby in the game’s first half, you are doing something that will hurt Ellie. Whether you control Abby or Ellie in the game’s second half, after the end of Seattle Day Three for Ellie, you are doing something that will benefit Abby.

But to take satisfaction or at least closure from the end of this story, you have to at least accept Abby’s story as being valid. If you disliked the idea of being ‘forced’ to play as Joel’s killer, you will have to get over that to enjoy the ludic highlights and more selfless quests of The Last of Us Part II, counter to the first half where your favourite character was doing mechanically engaging things for all the wrong reasons. You can decide you hate the Abby parts of the game if you want. But if you do then you my friend are at the very least missing out on some of the best zombie game levels I’ve ever played.

There are smaller and more mechanical instances of the game subverting how you play it that are no less interesting.

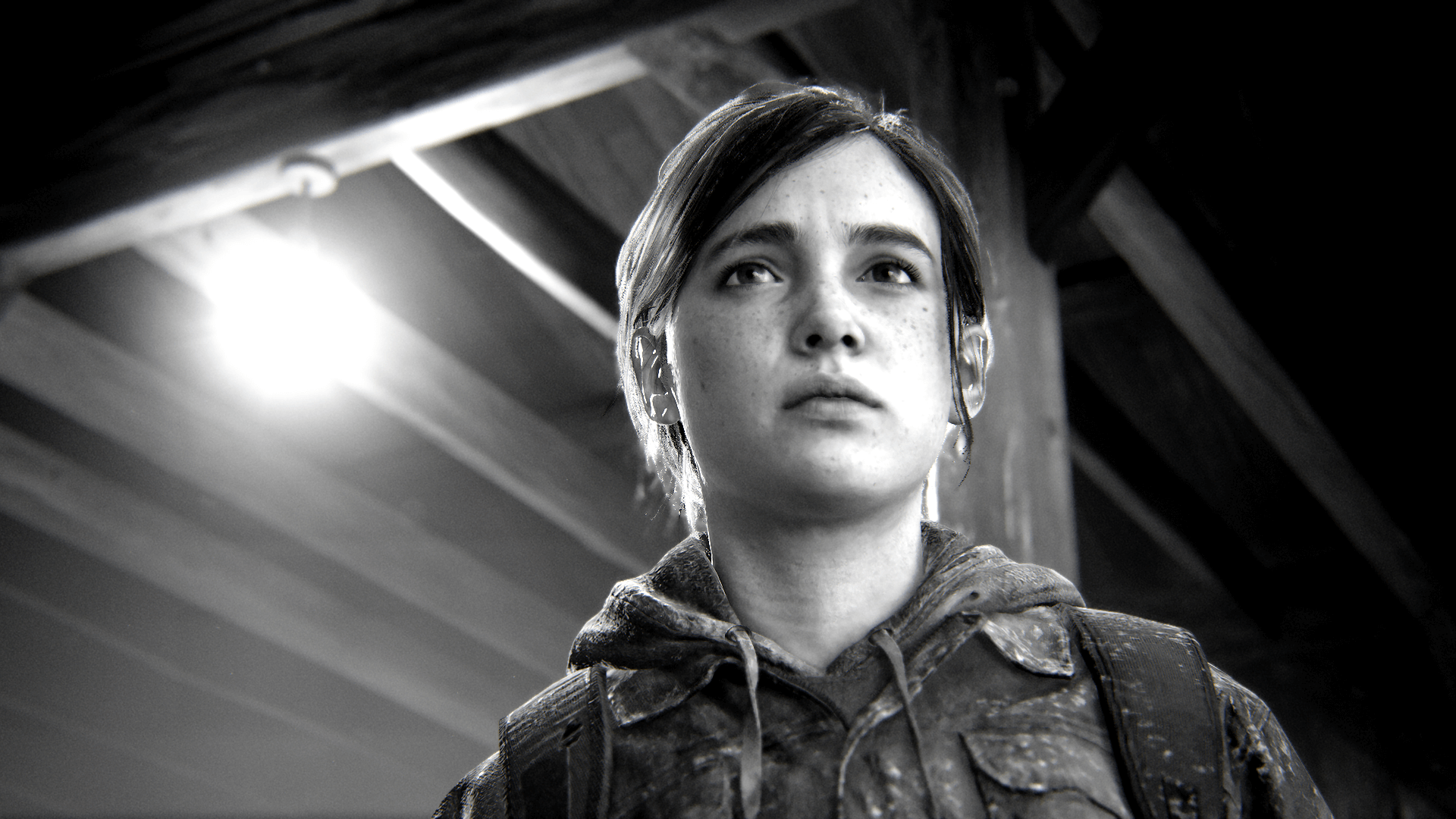

Seven or eight hours in, a flashback puts the player in control of young Ellie again, a year after the events of the original game. Joel is taking her to a birthday surprise in the form of a museum he has found and so begins a section much like the mall sequences of Left Behind, where the player interacts with items and explores the exhibits. Ellie then insists on exploring the building opposite, which Joel has not checked yet. The pair end up separated. As Ellie, you creep through a far less welcoming museum, sinister messages scrawled on the walls and indistinct sounds emanating from within. Then you start picking up bits of cloth.

Now although it stands to reason that there would be fragments of cloth lying around, these are the kind that get added to your inventory as a crafting ingredient for health packs and molotovs. At this point I tested and Ellie was now able to unholster her handgun, which had five rounds in it. You can also fire it. I immediately surmised that this Edith Finch-esque story section was going to lead into a combat encounter. That’s the only reason the game would start giving me consumables and let me draw my weapon, surely – I know how these things work.

You gingerly pick your way through the decrepit exhibits and are hit with a jump scare – except it isn’t a clicker or runner, but a wild boar that charges past Ellie and round the corner out of sight as Joel manages to get the door open, a cutscene plays and the flashback ends.

I never needed the resources, and I never needed to use the weapon. The genius of this red herring was that because of my familiarity with the game’s mechanics, and games in general, I was certain I would need them. If I had not picked these up I would have been less likely to anticipate combat, and been less on edge. The game used my relationship with the mechanics to put me in the same mindset as Ellie would have been, unsure of what was going to happen and preparing just in case. This trick created a shared expectation with the character.

An even more striking example takes place later with what feels like a breaking of the rules. As present day Ellie, you enter one of the many abandoned buildings to scour an apartment for supplies. Being a careful player in general I slowly move through any new territory, taking in the corners and assessing cover. The apartments are generally safe spaces, but you never know. Reaching the back wall of the flat I spot an upgrade station and, considering the apartment examined, hit triangle to go into the upgrade menu.

However, as I am scrolling through the tabs, wondering where to spend my upgrade points, the enemy awareness indicator flares and suddenly there is shouting and chaos behind me as I am torn away from the workstation and into combat. Ellie has been ambushed, while I am in a menu. Three WLF deserters hidden behind a hitherto locked door have jumped me and suddenly I am crouched behind the sofa trading shots.

This breaks all the rules and it is fantastic. If I’m not safe at an upgrade station, tinkering in my menus and mulling over aim stability versus clip size, then nowhere is safe. That should be obvious, in a country that the cordyceps infection has broken over its knee, and in a city in the midst of a civil war. Seattle isn’t Jackson, with its defensible walls and organised patrols. Violence can explode anywhere, at any time, and this violation of something I take for granted – that when I am in a menu I am safe – drives that home effectively. Later I found that even away from this scripted moment if I tried to interact with a workbench while enemies were nearby, I could but they would notice me. It actually reminded me of Dark Souls and Bloodborne, where there is no pause button and everything carries on around you when you’re in your inventory, making swapping out gear outside of a hub a risk.

I thought of this every time I visited the upgrade desks after that, and it set my nerves jangling for the next couple of hours of gameplay. With my preconceptions thrown out the window, I really didn’t know what was going to happen.

One area where The Last of Us Part II seems preoccupied with subverting a well-known game norm is in the sections where you squeeze through a tight space to progress. Those sections people say are so the next bit of game has time to load in. When you play as Abby before encountering the horde, you begin to squeeze through one and suddenly find a frozen corpse, seemingly Infected, is wedged in there with you. As Ellie in a flashback later on, a Bloater smashes through the cheap drywall of a hotel conference centre you’re squeezing through and you’re thrown into a boss fight. Best of all, as Abby pushes through another section like this, a Clicker begins jostling toward you and you have to frantically start pulling back on the stick to get out of there and into a position where you can fight it. I am sure there was a pitching session where people on the writing team were trying to dream up some of the most horrible situations they can imagine being in. Being jammed into a tiny space with a mindlessly ravenous monster dragging itself toward you is a good contribution if that was the case.

But all of these sections are doing the same thing – setting you up to do something you’ve done in lots of Uncharted games and the like, before interrupting you in the middle of it and turning it into a nightmare.

In the characters it has you play and what it does when you absent-mindedly act in ways videogames have let you act uninterrupted hundreds of times before, The Last of Us Part II makes sure you know it knows how you’ll be engaging with it. I find myself self-conscious of my actions in the game beyond the much-discussed morality of its central conflict, feeling like anything could happen in what is at its heart still a linear game.

This is extremely effective in a game relying on horror elements. More than anything, it made me really consider who I was playing as – and look forward to Abby’s half of the game more than any other part of my second playthrough, as without any prejudices toward playing as a new character I could really relish the greatest adventure in the game.