InnerVoid Interactive aim to follow a rich vein of indie games into the exploration of real-world settings and themes with That Day We Left.

I think it’s fair to say that independence in videogame development can offer the freedom to visit places and tell stories that aren’t commonly seen in more expensive, more risk-averse, large-scale games.

Unsurprisingly, games with this kind of independent flair are amongst the most frequently requested and eagerly anticipated for discussion on the Cane and Rinse podcast.

Many such games tackle modern, resonant themes in fantastical or otherworldly settings. I’m thinking, in particular, of Tale Of Tales’ The Path and Bientôt l’été, or even Camoflaj’s République, but occasionally we see real-world themes mirrored by real-world (or pseudo-real-world) settings.

Never Alone (Kisima Ingitchuna) is an interesting alternative to the Tale Of Tales style, in that it adopts a real-world, Alaskan setting to retell Iñupiaq folklore. Upper One Games punctuated the story with clips, photos and stories in order to help the player relate the game’s events to the lives of real-world Iñupiaq peoples. This isn’t perhaps subtle, but it is a different tack to games like The Path or Bientot L’Ete.

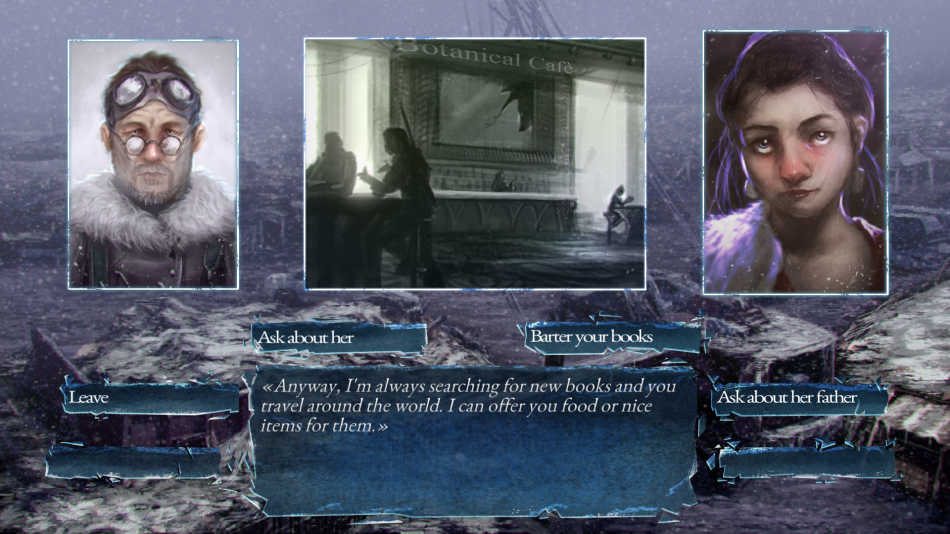

On the surface, InnerVoid Interactive’s first game, ICY shares Never Alone’s frozen tundra setting. The White Wasteland, however, is a non-specific location after an apocalyptic event. The player is tasked solely with surviving, and while survival games and post-apocalyptic settings may be ten-a-penny in the past few years, it’s not exactly the stuff of my day-to-day.

Where ICY succeeds is in grounding the setting through the game’s tone. Channelling player input predominantly through dialogue choices added to my feeling of helplessness, or at least vulnerability – encouraging proactive decision making, but with uncertain outcomes. The desperation of the situation was never far from my mind and that helped stave off any notions of this narrative as far-fetched or lacking realism.

The previously mentioned games tackle real-world themes or real-world settings, but not both. Valiant Hearts: The Great War may have a sense of whimsy, but there’s no denying that it’s setting, story and themes immediately resonate as being based upon real events. A period (1914-1917) French setting punctuated, like Never Alone, by images and information of life during The Great War helped bring me into the story being told. That story, recreated from letters sent during the First World War, felt genuine to the setting and helped bridge a divide of time and context in a different way to documentaries or books.

Whether it’s Valiant Hearts’ Great War setting, or the real-world conflicts of Call Of Duty or Battlefield games, there is seemingly an acceptance that portrayal of historical conflicts is fair game. But when Activision and EA DICE shifted their respective series into the modern era it’s notable that the antagonists became fictional nationalist splinter groups, private military corporations and terrorist organisations.

To corroborate the decisions of Activision and EA, when Konami and Atomic Games first revealed Six Days In Fallujah, there was much discussion over the use of ongoing or recent real-world conflicts and settings in videogames about war.

I’d argue that film, as a medium, has an easier time of tackling modern conflicts. Perhaps this is because it’s easier to provide a balanced view of conflicts (that, for many, sit in ethically or morally grey areas) when the audience is not holding the gun, so to speak.

Nonetheless, partisan, unilateral and jingoistic approaches are not uncommon in film-making, under the auspices and licence of artistic vision. Take any civil or international military confrontation of the past 70 years and you’ll likely find contemporaneous films depicting and commenting upon them.

Not to be kept from providing insightful commentary on modern warfare, 11 bit studios and their publisher, Deep Silver, decided to switch the perspective from the soldier to the civilian.

This War Of Mine looked squarely at the lives of the people caught in the crossfire of the Bosnian War. Whether the war was being fought on behalf of the very people it hurt the most I’ll leave to more qualified people to decide, but there’s no denying that This War Of Mine put the plight of civilians front and centre.

Scrabbling to survive; risking life for the smallest chance of finding food, medical supplies, equipment or other survivors was always tense. It is important that the player never has direct control of the outcomes of their actions in the way they would in a Call Of Duty or a Battlefield.

The survivors are victims of this war without the ability to know when or if there will be (much less bring about) an end to it. By presenting war in this way, This War Of Mine gave me a window into experiences that I can’t possibly comprehend, but are nonetheless the very real and terrifying experiences of Bosnian people some 20 years ago.

Even having removed the lens of the soldier from consideration, 11 bit studios decided that setting This War Of Mine in places affected by three years of horrific war a little over two decades ago was not appropriate. Pogoren, Graznavia, may not be a real place, but it very definitely was intended to represent one. Like Valiant Hearts, This War Of Mine felt genuine to its real-world themes and setting.

Of course, war isn’t the only realistic backdrop for games seeking to explore the difficulties of day-to-day lives. Papers, Please would be one such example of a developer (3909) challenging the player to face up to the reality of (amongst many other themes) segregation, non-democratic governance and political bureaucracy, albeit in the pseudo-real-world setting of Arstotzka.

Richard Hofmeier’s Cart Life obviously goes hand-in-hand with Papers, Please in this regard. The setting, despite not specifically being a real location, offers verisimilitude to match the down-beat tone and gameplay.

What I like most about these games is that player reflection doesn’t happen only after the fact; due to the setting being framed in reality, the player is encouraged to reflect on how it compares to their own real-world surroundings and situation.

This brings us back to InnerVoid Interactive, the developers behind ICY. I mentioned earlier that, despite ICY’s fantastical post-apocalyptic setting, it managed to retain a grounded tone due to similar feelings of helplessness that I also described in response to This War Of Mine.

Fitting, then, that InnerVoid’s next project should be centered on a group of Syrian refugees, forced to flee their homes in search of safety in Europe.

That Day We Left is currently in development, but (Lead Designer) Nathan Piperno hopes to build on the experience of making ICY. The story of refugee, Rashid, guiding his family to safety seems perfectly suited to the sort of narrative-focused, resource-management and decision-based gameplay of ICY. Via email, I asked if the mechanical aspects of ICY (dialogue choices, resource management, character levelling) would be the basis for That Day We Left:

“The games are different in many aspects, but we can say that our experience with ICY will be useful. We’re looking to learn from our mistakes and improve on what we did right.”

ICY’s isometric 2D environments were a big part of setting the scene for my experience with the game. Surprisingly, while the artwork for That Day We Left looks equally interesting, it’s a big departure from the previous game, and (evident from early screenshots) uses 3D rendering.

InnerVoid are taking this big step in their stride though:

“Actually it [moving from 2D art to 3D environments] was pretty easy because new people joined the team and brought their experience with them. We’re quite happy about it, since working with 3D graphics gives us more freedom.”

It’s still early days, the game having only just been announced, but Nathan expects that video footage of the game will be available soon. Of equal interest to me is the theme that That Day we Left is looking to explore: that of modern day refugees.

Again, like ICY, this aspect of the game lends itself to portraying the complexities of group dynamics. In this case, however, the game will be based upon the stories of real-life people.

I asked Nathan why he and InnerVoid chose this topic, in particular, for their game:

“We thought we could make a good game out of such a theme, and that there’s an interesting tale to tell. We’re mostly focused on improving ourselves and creating better games, but we also hope that That Day We Left will promote unbiased discussion about this real-world issue. Our main focus is to create good games and good experiences. Anything else is secondary to that focus. We’re videogame developers, not only storytellers, so we have to be sure we are working on a good game.”

I hope you’ll agree that independent developers such as 3909 (Lukas Pope), Richard Hofmeier, 11 bit studios and InnerVoid Interactive are pushing videogames into exciting real-world places.

Even if they have to follow the AAA lead of changing a place name here or there, it’s clear to me that their games seek to reflect the stories of people who aren’t often represented in this medium. I, for one, will be keeping a keen eye out for more news on That Day We Left.