Subset Games’ 2018 kaiju puzzle game might seem simple, but a couple of hours with it show immense depth beneath the cute pixel art and grid-based battles. Not to mention if you play it for, say, 50 or more hours like I’ve done.

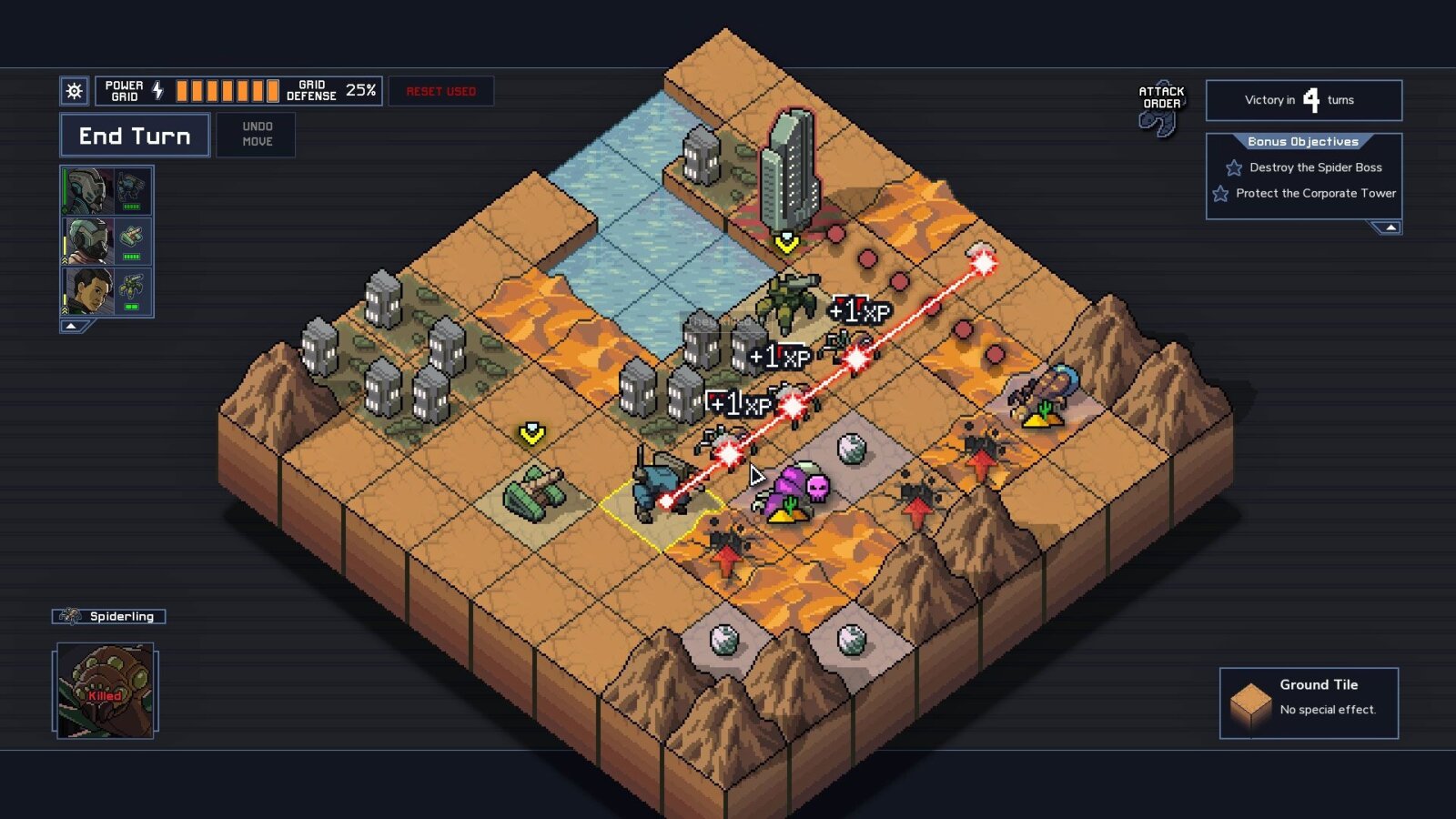

In Into the Breach, you control mechs traveling back in time to save the Earth from being overrun by interstellar building-sized bugs called the Vek. Its mix of easy-to-play and hard-to-master rules, just the right amount of RNG-induced tension applied to its overarching thesis of providing perfect information to the player, and intelligent achievements system provide potentially hundreds of hours of challenge.

Its depth also extends to its story, which is the optional part. It is totally valid to ignore the story and instead immerse in a richly rewarding and often tough-as-nails game about knocking enemy pieces out of the way before they can land their attack. Treat it like chess, but (in my opinion) more fun. However, there are some top notch stories to be uncovered, albeit briefly sketched – which is one of the strengths of the game.

As you journey to each island you get a very short briefing from the CEO of the respective corporation that runs it. These give you an idea what life might be like – at Archive Inc., for example, I imagine the residents of the buildings might usually be going to work refurbishing and restoring tech from “Old Earth”, which the island’s military even brings to bear against the Vek.

There’s an industrial island, and an icy one – but my favourite leader is Jessica Kern. She leads the RST Corporation, which is terraforming and transforming their island so that the environment itself will work against the mechs. Having recently read (and then watched) Liu Cixin’s The Wandering Earth, I’m pretty into science fiction where entire societies have somehow found common ground in order to make difficult decisions and work together against an existential threat.

You can see how Kern is getting the job done – she suffers no fools. In fact, if you screw up objectives or worse get her citizens killed, she doesn’t mince her words telling you off and sometimes makes it clear you’ll be heading straight for a dressing down after the battle: “About that terraformer… make my office the first stop when you return to base.”

She’s also sympathetically furious when one of your pilots is killed in action though, vowing to make the Vek pay. And more than any of the other island leaders she is confident in her own methods of winning the war, often suspicious of why your mechs are even there – “One of your ‘Time Pods’ has appeared on sensors. Perhaps this one will shed truth on why you’re really here.” Things like this are what makes the characterisation work in this tiny game – this is a textbook action movie B-character.

And Kern, through sacrificing the island she and everyone else from RST calls home, gets really close to beating the Vek. She’s even there at the end with you, dispatching a bomb the islanders have developed to blow up the hive the aliens have created within a volcanic island.

Which is what really brings home the stakes at the heart of the game’s plot. Kern, RST Corp, the folks from Archive Inc with their classic planes and tanks: they didn’t do it. The first words you see when you fire up the game are “Humanity: Destroyed. Vek Threat: Unstoppable. Mission: Failed.” As you play the game you are seeing and fighting alongside the final defenses humanity could muster before they were totally overrun. It adds pathos to see a population cobbling together what defenses they could, and to have the knowledge that it just isn’t going to be enough – unless you manage to change the timeline.

And if you fail your run, losing the grid or all your pilots – that’s canon. Within the logic of the game, you are time traveling back to different timelines saving as many as you can. But the ones where you lose, your pilots remark on them, remember them, that really happened and it is on you. It is a very interesting way of adding weight and consequence to time travel, something that is often used as plot armour to alleviate those things.

It also gets you pretty attached to your pilots – my versions of Bethany Jones, Archimedes and Lily Reed have a little stat showing how many times they’ve fought the final battle and how many timelines they’ve saved. They also remark on it when you bring them to another timeline, talking about how they are ready to do it all over again. I just love the idea of your hero actually having been there, done that maybe dozens of times before. It is a unique twist on time traveler fiction, and unlike most media that is concerned with mechs and gundams, makes those inside the machines as interesting as the machines themselves.

The remarkable soundtrack from FTL veteran Ben Prunty is hugely supportive of the sense of stakes. A mix of stirring guitar and synthesizers provides the backdrop. With large sections of each run consisting of me staring at the mech and enemy arrangements thinking how best to use my three moves and three attacks, there is plenty of opportunities for the music to sink in. The occasional emotive swells and gradual builds of tension work perfectly to convey an atmosphere where gigantic machines and alien insectoids are – to the player – essentially frozen in time, a crucial moment made a tableau where you have to make the exact right decisions or see buildings full of people obliterated.

Which is something you’ll be marked on, as well. The screen you get when you beat the game actually tells you the final population of Earth – how many lives you saved. The developers have talked about how they designed the game with collateral damage as the lose condition, and how they took time to tune and refine the systems in a way that would encourage players to prioritise protecting the buildings. It is essentially an inverse philosophy to many blockbuster movies, where cities are flattened in the background while we watch the heroes do battle.

The small numbers lend consequence as well: The only thing between these islanders and doom is a mech that can take maybe two hits. You can always level them up, sometimes to 7 hitpoints, but you’ll be facing more powerful creatures by then and bosses that can one-shot all but the sturdiest mechs. The sense of fragility in the face of a powerful foe this creates is quite impactful.

Most of your time in this game is still about knocking pixel art bugs out of the way before they destroy your power grid. Based on interviews and developer talks, Subset put a lot of thought into not only why the failstate was primarily about losing the buildings and their inhabitants, but also making the player care about that. It is impressive to see the degree to which the characters, story beats, minimal narrative and the mechanics often cohere in service of that.

Really interesting read, Jon! I definitely reads like someone who has played 50+ hours of Into The Breach! There aren’t many games that I can recall from the top of my head where the lose condition is actually canon!

I have the game myself and need to get around to finishing it. Whenever I do play it, I rename all of the pilots and mechs after Pacific Rim characters. 😉

Thanks for the kind words Howard! I must say those hours have gone up since I wrote this as well.

Interestingly Star Renegades, which just came out, has a similiar approach to canonical failure where each time you lose you’re going to a different alternate universe.