You know the frustration of returning to a game you’ve beaten before but finding you’ve forgotten how to solve it? Joshua Robinson looks into why this occurs.

The last trophy I earned in Portal 2 was on May 16, 2011. That isn’t a definitive, ‘last time I played Portal 2’ mark, but I most likely haven’t played the game in seven years.

I, of course, remembered Cave Johnson, Wheatley and GLaDOS. I remembered some set pieces. I remembered aspects of the gels; there is a speed-up one. My memory of the game’s puzzles, however, had faded entirely. I couldn’t recite any of the solutions or the problems that necessitated them.

I went back to Portal 2 recently. When I was back in that world with plants overtaking a ruined Aperture Laboratories, the sounds of turrets firing, GLaDOS heaving snide comments at Chell, I still couldn’t remember a thing about those chambers.

It wasn’t quite like playing Portal 2 for the first time, but it is close. I found myself stuck on puzzles that I know I had cleared before. There has yet to be a chamber where I’ve said, “Oh! I know the solution to this one!”

When did all of this forgetting happen, and why?

Unfortunately, most research on puzzles and memory is not done with Portal 2. They are done with the Tower of Hanoi. The goal of the game is to move a stack of discs to a new post in a set of three. Only one disk at a time can be moved, the top most disk of a stack must be moved first, and larger disks cannot be place on top of a smaller disk. Bringing this back to Portal 2, think of each different variation (number of disks, which rod to rebuild the tower on) as a different test chamber.

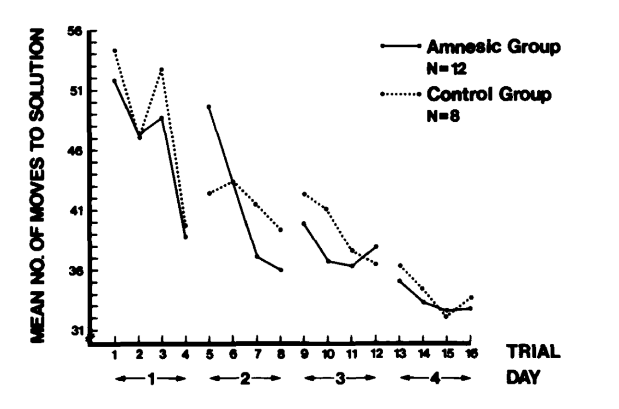

In the paper Different Memory Systems Underlying Acquisition of Procedural and Declarative Knowledge researchers used various iterations of the Tower of Hanoi to examine how cognitive skills are acquired by contrasting the ability to find optimal solutions between twelve amnesic patients and eight control subjects over time.

Amnesic patients show a capacity to learn the puzzle just as well as the control group despite the fact that “8 of the 12 (amnesiac) patients denied having ever seen the puzzle previously when queried at the start of the second testing day.” These results led the researchers to posit:

“.. that with practice amnesic patients and control subjects become better able to derive the solution to the puzzle without necessarily remembering explicitly the puzzle, the component steps of the puzzle, or a set of explicit rules for solving it. That is, we conclude that subjects are not looking at particular configurations and thinking: “Oh, I know this one. What I do here is to move block X to peg Y.” Rather, they derive a solution from each configuration, more efficiently and more successfully each time.”

People seem to not commit solutions of puzzles to memory. Only the intrinsic skills required to solve the puzzle are remembered. Why was I not able to remember the solutions to Portal 2’s chambers? It isn’t a failure of memory. It is a product of how people process puzzles. Completing them once or twice only commits the abilities required to solve the puzzle to memory.

While the Tower of Hanoi experiment answers the question on why I couldn’t remember the solutions to Portal 2’s puzzles, it doesn’t answer the question of when I forgot them. I still knew the solution to each chamber immediately after solving the chamber. Where did that go? It was likely never committed to long-term memory.

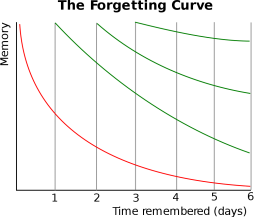

Dr. Hermann Ebbinghaus published a book in 1885 called Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology where he collected data on his own memorization of nonsense syllables in order to create a mathematical formula that can chart the process of forgetting. The graph is known as the forgetting curve. Upon initial learning of a fact, the graph shows how long it takes for that memory to degrade. Without repeated learning that fact is stalled in short-term memory and slowly lost. The experiment was recreated by Murre and Dros in 2015.

Dr. Hermann Ebbinghaus published a book in 1885 called Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology where he collected data on his own memorization of nonsense syllables in order to create a mathematical formula that can chart the process of forgetting. The graph is known as the forgetting curve. Upon initial learning of a fact, the graph shows how long it takes for that memory to degrade. Without repeated learning that fact is stalled in short-term memory and slowly lost. The experiment was recreated by Murre and Dros in 2015.

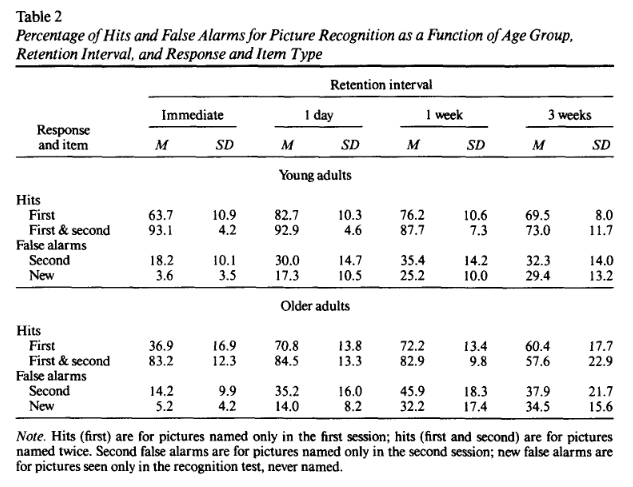

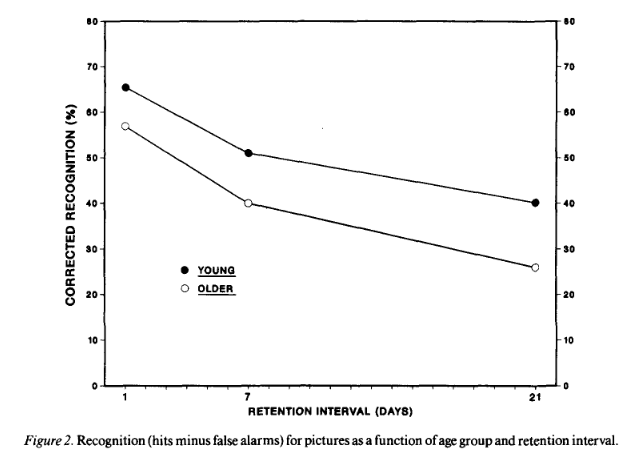

This kind of decline is similarly shown in Mitchell, Brown and Murphy’s experiment on the effect of repetition and memory. The subject population included 48 young (18 to 34) subjects and 48 older (57 to 83). Each subject is shown two sets of slides containing images of everyday objects. Some images are shared between these sets. The subject is shown a third set of slides either immediately, one day, one week, or three weeks after and asked to identify which images from that set also appear in the first set.

The above table contains the averages (M) for each group of subjects as a percentage. Hits are successful identification of pictures that appeared in the first set. False alarms are incorrect identifications of only second or third set images. Repeated slides have a higher hit rate than slides shown once except for at three weeks in older adults. Showing that even one set of repetition aids in memory retention. At the one day interval there is an increase in retention likely due to sleep’s effect on memory, but there is also an increase in false alarms. Generally one week and three week time points have decreases in positive hits. False alarms either increase or stay roughly the same at these time points.

The information from Table 2 is made into this easier to understand graph showing an average curve of forgetting. One day post learning something will be the highest percentage of retention, but will drop continually after. Say you complete Portal 2 in one day. The next day you’ll remember about 65% of chamber solutions and at 21 days you’ll remember around 40% of them.

Which is what likely happened to my memories of Portal 2’s solutions. I played the game and when I set the controller down the process of forgetting started. Continuing along until I couldn’t remember the solutions anymore. I am enjoying going back and playing through what feels like a fresh-ish Portal experience. Sure. I know the plot. GLaDOS will still become a potato. I’ll never forget how to play the game or the mechanics of the Portal universe. However, the puzzles are surprising again.