“I didn’t just lose a child, I had a child.”

This is how Sara Curtis opens “In The Left Pocket, By My Heart”, an episode of the podcast ARRVLS, which chronicles her experience of losing her infant daughter over the course of a year, told in retrospect.

The death of a child is one of the last great taboos, but Sara’s account reveals a vital truth about that most tragic of subjects; that children who die are more than just the tragedy of their death, more than their unrealised potential and the exhausted timbre of their parents’ voices. Their child, however briefly, was a person.

The child possesses personhood in a way that precedes achievement or communication. It comes from the marvel of holding them and playing with them and scrutinizing every minute action or reaction as the first sign of a blossoming personality. It’s personhood by way of the physicality of shared space, and of what sharing space with another person can mean.

Games are good at spaces. Be it Rapture, The Cradle, Silent Hill, or even just a Washington mansion, most games are about crafting imaginary worlds and giving the player the tools to interact with those worlds. The beings occupying those spaces, however, have always been flimsy. Conversational systems in games are clunky and distant, and real-time graphics rendering and animation techniques still lag far behind the curve of the uncanny valley.

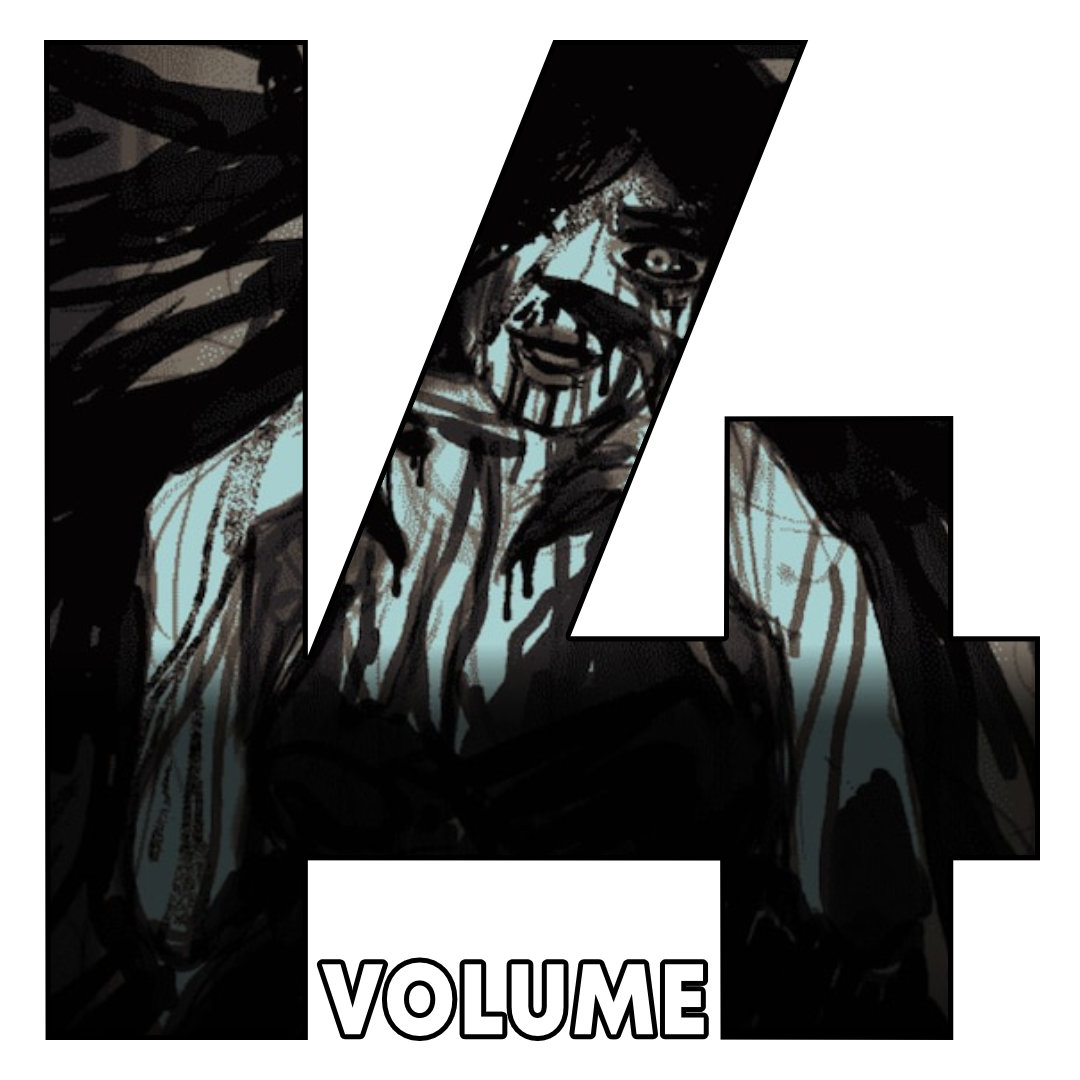

There’s something about what Ryan and Amy Green, along with a number of other contributors, achieve in That Dragon, Cancer that overcome these shortcomings.

That Dragon, Cancer tells the story of the Greens losing their five year-old son, Joel, to cancer. It explores the effect these experiences had on their family and on other people in Joel’s life.

It’s an achingly emotional experience, filled with fear and sorrow and hope. In lesser hands, gaming’s generally underdeveloped artistic vocabulary might have rendered this portrayal limp, directionless or even outright crass.

Instead, it’s a triumph, due largely to its focus on the personhood of the people it depicts. They feel real in a way I’ve never seen before in a game.

In a medium which has always struggled with humans, this game captures humanity to an awe-inspiring degree. Rather than in physical or spatial representation, That Dragon, Cancer finds its strength in digging deep into the emotional truths of its creators’ experiences.

The character models are geometric and faceless, leaving the voice acting and animation to do the heavy lifting. As with Cibele, many of those voices are provided by the actual people rather than actors; but here these amateur performances are stunning, always expressive and convincing in such a way that asserts authenticity.

At times, it feels uncomfortably voyeuristic. We don’t know how little distance there was between the unbearably painful events the game portrays and their recording, but it’s inevitably close enough that, as the game escalates, the unfiltered emotion of the piece becomes increasingly overwhelming.

But these are all just ways of explain the most important thing: this game feels like it has real people living in it. Sharing these rooms with people who feel and sound real, watching the ways in which they react and change and interact with one another, is an eerie revelation.

At the very least, it’s impossible to ignore that this game is a chronicle of real events and emotions. More than that, it’s an evocation; it recreates, giving life to the most painful experience of its creator’s lives. It is able to do that because in those experiences, Joel is still alive.

The game doesn’t shy away from the fact that the Joel within the game is, in fact, a phantom. You might round the corner and suddenly see him, then look away at the source of some sound cue, only to realise that he’s not there anymore. His portrayal has all the authenticity of the others in this game, but here there’s the added wrinkle of knowing that this child is dead, of wondering which of the burbles and squeals the in-game character makes were provided by the real person.

If That Dragon, Cancer feels like it’s inhabited by the humanity of real people, people whom the developers knew and loved with such intensity, and one of those people is no longer alive, the portrayal suddenly becomes something unprecedented. This feels like an echo of a child living on in script and animation and character model. It obviously can’t capture Joel’s internal life or his way of viewing the world, but it preserves the way his parents experienced his presence to a haunting effect.

Vitally, That Dragon, Cancer also justifies itself as a game through its use of play as a recurring motif. One of the most effective ways to communicate with a non-verbal child is through play. Thus the game can establish different layers of play within itself to communicate different things. The player plays with Joel, plays games which elucidate elements of the Greens’ story and plays through that story themselves, and each of these layers use play in different ways.

Some are games within the game, which evoke videogame clichés and re-contextualise them to explore different aspects of the core experience. They occasionally veer into being a kart racer, a navigation game and even a Ghosts ‘n Goblins clone with a control quirk that grants everything else in the segment an extraordinary depth of meaning. Others serve as a more direct form of communication with a character.

Most impressively, this level of ludic exploration never feels contrived or self-indulgent; it always manages to push forward into the core themes of the work in a fresh and earned manner.

If nothing else, the game is a quiet revolution in its treatment of faith. The Green family are very actively religious, and as medicine fails Joel, they turn increasingly to reflection upon God, torn between respect for God’s plan and desperate hope that it can be diverged from.

It examines the push and pull of hope in a higher power, the fear of insignificance in the face of that power, and even the tensions of the mutually exclusive ways in which people try to get what they need from their shared faith. I can’t think of any game which has reflected upon the substance of religious faith as beautifully as this.

That Dragon, Cancer is consistently a triumph in tackling all of its colossal subject matter. It wants to deal in loss and impermanence in the face of the infinite, in the ways in which tragedy both unites and isolates. It also chronicles the tiny, autobiographical details of their son’s struggles, as well as their own. I consistently found it to succeed; it communicates with nuance and curiosity, every scene being a deftly judged new avenue of expression and exploration.

There is an extent to which this game is granted significance by its weighty themes and subject matter. However, it earns that gravitas with its deft handling of the material. The gamer subculture has always struggled with this, but subject matter matters. What your work is about doesn’t necessarily determine how valuable it is, but it does determine how valuable it can be.

This places any subculture which values escapism in a tricky position, but it’s a factor any medium of communication has to understand. A work which achieves all of modest ambitions might still be worth less than a work which falls short of a much higher goal.

That Dragon, Cancer demands a level of empathy and emotional intelligence that most games would find prohibitive, but in meeting that demand you get the privilege of experiencing perhaps one of the most resonant game experiences ever created.

The only snags I encountered that lessened my experience were in the most humdrum, micro-level elements of the game design. The game never feels elegant or intuitive to interact with and the signposting is often lacklustre.

It often requires the least interesting kinds of adventure game interaction cycling to proceed, which detracts from the flow of the narrative and of the game. The few moments where it would benefit from feeling immediate and tactile are all bungled.

Its puzzles are obtuse, unwilling or unable to establish any sort of vocabulary, and rarely feel expressive or intuitive. The nuts and bolts of its mechanics are a chore to deal with, and it’s especially frustrating because the broader gameplay systems are functional and expressive, the art is beautiful, and the sound design and performances are immaculate.

The price of all the interesting communicative mechanical flourishes is that the team doesn’t seem to know how to work the meat-and-potatoes elements of design.

But, in this particular case, none of that really matters to me. What matters are the things Ryan and Amy Green have to say about love, life and death and all the questions most games would either shy away from handing or fumble in their inadequacy. What matters is the beauty of the thing these parents have made in memory of their son.

And what really, really matters is being next to Joel. It’s experiencing his physicality, playing with him, seeing him exist in some form that outlives the rest of him.

In this little space crafted within the game, a young man who was taken from the world far too soon can achieve some measure of immortality, touching lives far beyond those who ever met him. And for all that his parents ask of God, I think it might be the experience this game provides that might honestly be close to a miracle.

That Dragon, Cancer is available to buy for PC/Mac via their official site